Tokens of ghostwriting

Writing, talking, and rewriting like Herman Melville in "Scenes Beyond the Western Border" (1851-1853). Chapter 2.

In and out of his great American novel Moby-Dick (1851), author Herman Melville used the word tokens to describe individualizing marks that potentially reveal identity. Captain Ahab’s nemesis, the famous White Whale called “Moby Dick,” could be positively ID’d by two unique aspects of his physical appearance:

“… a peculiar snow-white wrinkled forehead, and a high, pyramidical white hump. These were his prominent features; the tokens whereby, even in the limitless, uncharted seas, he revealed his identity, at a long distance, to those who knew him.” — Moby-Dick, Chapter 41: Moby Dick

Head and hump gave him away to well-informed whalemen. That’s Moby Dick! All over the watery world, this “most deadly immortal monster” carried his identification with him on his own body.1

In Melville’s private view, elsewhere expressed, a body of text might also contain identity markers, in this case “tokens” of authorship. Melville alluded to textual evidence of this kind in one of the notes he carefully inscribed in his personal copy of Owen Chase’s Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-ship Essex:

Authorship of the Book

There seems no reason to suppose that Owen himself wrote the Narrative. It bears obvious tokens of having been written for him; but at the same time, its whole air plainly evinces that it was carefully & conscientiously written to Owen's dictation of the facts. It is almost as good as tho' Owen wrote it himself.2

Without specifying what they were exactly, Melville discerned enough “obvious tokens” in the 1821 Narrative by Owen Chase to convince him it had been ghostwritten for its putative author.3 We don’t know for sure what “tokens” Melville had in mind. Maybe he had noticed a brief passage or two of reflective writing, or the occasional melodramatic flourish. Or maybe the “tokens” had more to do with the basic mechanics of arranging words in coherent English sentences and paragraphs. For the most part, as Melville perceived, the action and descriptions in Chase’s Narrative are straightforwardly presented. The editorial restraint apparently shown by Chase’s uncredited collaborator (presuming that Melville was right in believing Chase had one) clearly pleased Melville, who regarded whatever evidence or “tokens” of ghost-authorship he had detected in the published version as “obvious” but unobtrusive.

The first chapter of my present study focused on the narrator’s quest for one good listener in the 1851-3 magazine series “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” and identified close parallels of language and theme in the surviving record of Herman Melville’s friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne. Here in the second chapter I will examine some probable tokens of ghost-authorship in the first installment that appeared in the June 1851 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger. Although every one of them has a parallel in the known writings of Herman Melville, as will be demonstrated, I do not claim that such correspondences “prove” Melville’s authorship of works long credited to Philip St. George Cooke. I do mean to put Melville in the mix of likely candidates. Other possible candidates will be considered in a later chapter. Before we look at any tokens, however, I hope to establish the essential reasonableness of my claim that Cooke or any would-be author in the 19th century might legitimately and honorably take credit for a literary work substantially composed by another writer.

Using the services of a professional writer was a mainstream route to getting published in the 19th century, especially in the genre of travel and exploration. What we now denominate ghostwriting was a well-established trade in Melville’s time, although nobody spoke of “ghostwriting” or “ghostwriters,” in print at least, before the twentieth century. As Michael MacDonagh recognized in 1903, “Authors’ ‘ghosts’ have, perhaps, been with us always.4 All through the 19th century, publishers routinely employed talented writers to give shape to sensational content and revise ragged manuscripts with the aim of making them into readable and hopefully marketable books.

To early critics, Melville’s first book Typee (1846) seemed amazingly polished, maybe too polished for the work of a common sailor as the author was then supposed to be. One English reviewer, evidently forgetting that Typee had first appeared in England as the Narrative of a Four Months' Residence Among the Natives of A Valley of the Marquesas Islands, felt Melville’s way-too-literary debut must have been professionally “embellished” by a another, more experienced hand under contract with Wiley & Putnam or the Harpers in New York City.

“We return to the amusing volume of Hermann Melville, picking up as we proceed fresh evidence of the truthfulness of the narrative, though we cannot divest ourselves of the impression that the narrative has been embellished by some literary employé of the American bookseller.”5

In America as well as England it seems to have been an open secret in literary circles that many of the most popular works of travel and adventure were more than “embellished,” being in fact manufactured to order by professionals. The extent of a ghostwriter’s involvement must have varied considerably, depending among other things on the abilities of would-be authors and the expectations or demands of their publishers.

In generic terms, the products of such arrangements might be classified as collaborative writing, if other contributors are credited or somehow known; or ghostwriting, if not. As neither term existed yet in Melville’s day, I could not help wondering what they called those expert embellishers, improvers of style and grammar, and content-creators back then, whether acknowledged or anonymous. A bit of digging in digital newspaper archives turned up the answer I ought to have guessed:

Editors!

Ghostwriters in the 19th century were considered to be editors. As articulated with wonderful frankness in a column of the New York Commercial Advertiser for June 14, 1837 titled “Authors and Editors,” the task of writing up another person’s story or narrative, what today we would call ghostwriting, was then deemed a proper and useful branch of editing. In the excerpt below, the columnist (presumably William Leete Stone aka “Colonel Stone,” respected author, journalist, and owner-editor of the Commercial Advertiser) ably defends the occupation of ghostwriting and halfway admits to having done a bit of it himself, on the sly.

So too in the case of Riley or Morrell—it is readily intelligible that these worthy personages, being men rather of action than of narration, and much better qualified to get themselves into situations where they would be likely to pick up matters worth telling, than to tell of what they had picked up, would very naturally and properly seek the assistance of others, who had cultivated a more intimate acquaintance with the school-master, in order that they might present themselves with a better grace to the public, as the narrators of strange adventure in foreign parts; and although it should be generally known that the actual labor of fashioning their discoveries, or achievements, or sufferings, into respectable English, was performed by another hand, there would be no objection to the display of their own names on the title-page. Of editing such as this we can perceive the propriety, and the object, and the usefulness—and we have done some of it in our day, perhaps in cases of which nobody entertains a suspicion.

Obviously, and fortunately for us, Colonel Stone did not mind naming names. His 1837 column identified James Riley and Benjamin Morrell as exemplary “men rather of action than of narration” whose well-received books of real-life nautical adventure were in fact ghostwritten for them by other hands. The works here alluded to are Riley’s Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce (New York, 1817) and Morrell’s Narrative of Four Voyages (New York, 1832). Earlier in the same column, Stone openly acknowledged the ghost “editors” who had done “the actual labor” of writing for Riley and Morrell as Anthony Bleecker and “our old friend Samuel Woodworth,” respectively.6

The larger aim of the 1837 editorial in William Leete Stone’s New York Commercial Advertiser was to complain about the deceptive practice of naming a popular author as “editor” merely to sell more copies of a work by a relatively obscure writer. What raised Colonel Stone’s ire was a new London edition of Nick of the Woods (issued by Melville’s future publisher Richard Bentley) where novelist William Harrison Ainsworth receives questionable credit on the title page as “editor” of an otherwise unpretentious and quintessentially American work by Robert Montgomery Bird.

Before he got to railing about the duplicity of Brits in promoting fake editors, Colonel Stone distinguished two kinds of editorial jobs, different but in his view equally legitimate. One is the traditional academic or scholarly work of assembling and evaluating canonical literary texts, “elucidating obscure passages by explanatory notes,” providing biographies of major authors like Swift and Dryden, and occasionally censoring any bawdy or blasphemous language “which would prove offensive to the more fastidious delicacy of a later generation.” In Stone’s very classical view, that kind of editing encompassed the work of collating, compiling, explicating, and expurgating texts. All these jobs might still be performed by a modern editor doing traditional scholarship. The other kind of editing as Stone described it in 1837 is just what a modern ghostwriter does.

When Melville’s narrator Ishmael needs readers to believe in the awful power of a Sperm Whale to smash and sink a large whaleship, he leads with the real-world example of the American whaler Essex, in actual fact stove by a whale. For documentary evidence of that catastrophe and its horrifying consequences, Ishmael in chapter 45 The Affidavit cites and footnotes the “plain and faithful narrative” by Owen Chase.7 Ishmael’s endorsement accords with Melville’s private evaluation of Chase’s 1821 Narrative as “carefully and conscientiously” drafted, although Ishmael stops short of revealing what we now know Melville privately thought about its bearing obvious tokens of ghostwriting.

Along with Melville’s handwritten note on the probable ghost-authorship of the Essex Narrative, the column “Authors and Editors” in Stone’s New York Commercial Advertiser may helpfully illuminate the extent, literary value, and general acceptance of ghostwriting in the 19th century. This 1837 editorial and numerous other examples of ghostwritten travel narratives tend to support the plausibility at least of my hypothesis that somebody other than cavalry officer Philip St. George Cooke ghostwrote the 1851-1853 magazine series “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” for him. Originally published in thirteen installments in the Southern Literary Messenger, “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” became (after light but in places significant revision) the second half of Cooke’s 1857 memoir Scenes and Adventures in the Army.

If more historical examples of ghostwritten books are needed for this my Wild-West version of Ishmael’s chapter 45 “The Affidavit,” we don’t have far to look. Benjamin’s wife Abby Jane Morrell released her own Narrative of a Voyage to the Ethiopic and South Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Chinese Sea, North and South Pacific Ocean (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1833), ghostwritten by Samuel L. Knapp. Benjamin’s ghostwriter Samuel Woodworth, as discovered and discussed by James Fairhead in The Captain and “the Cannibal” (Yale University Press, 2015), also authored much of the Voyage of the United States Frigate Potomac under the Command of Commodore John Downes (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835) “nominally written by Jeremiah N. Reynolds.”8

In the category of far-west travel and adventure, the backstage work Nicholas Biddle did to produce the official story of Lewis and Clark in the History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark (Philadelphia, 1814) provides an early instance of extensive re-writing conceived as “editing.” There, yet another hand, that of “Paul Allen, Esquire,” received sole credit as editor on the title page. Thirty years before, the autobiography of iconic American hero Daniel Boone had appeared in The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke (1784). Boone’s narrative, ghostwritten for the illiterate frontiersman by an enterprising but ill-fated farmer, teacher, and surveyor named John Filson, would be extracted and repackaged all through the 19th century. When Herman Melville himself was farming and teaching for minimal pay, Washington Irving famously gave Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville one thousand dollars for his manuscript journal (now lost) which Irving promptly rewrote as the Adventures of Captain Bonneville, or, Scenes beyond the Rocky Mountains of the Far West in 3 volumes (London: Richard Bentley, 1837).

Frontier literary partnerships were not always so productive, of course, or happily conducted. Santa Fe trader Josiah Gregg first turned over his manuscript jottings for the work that became Commerce of the Prairies to Count Louis Fitzgerald Tasistro. But Gregg, being an honest and plain-speaking man of business, disliked the fictions that Tasistro would habitually insert as improvements on Gregg’s matter-of-fact narrative. On the recommendation of William Cullen Bryant, Gregg then hired John Bigelow who soon found, as he recalled fifty years later, “that all I had to do was to put his notes into as plain and correct English as I knew how, without in the least modifying the proportions of his affirmations.”9

However resolved, or not resolved, tension between reality and romance is practically a trademark of ghostwritten travel narratives. As William E. Lenz has observed, the 1832 production of Benjamin Morrell’s Narrative of Four Voyages represents a fascinating merger of practical and poetic agendas. Here Lenz calls attention to the ghostwriter’s contribution of the “imaginative” part in this particular fusion:

As a work ghostwritten by Samuel Woodworth—journalist, playwright, and author of “The Old Oaken Bucket,”—Morell’s Narrative itself replicates the joining of the factual to the imaginative. 10

Indeed, some contributions of imaginative content by Woodworth reportedly were purged before publication, being deemed overly literary for the narrative of a sea captain. For example, Morrell’s ghostwriter went overboard with the Shakespeare quotes, as later recollected by a New York editor with inside information:

We supposed it was generally understood that "Morrell's Voyages" was mainly written by SAMUEL WOODWORTH, the poet. MORRELL was a very good sea captain, but made no pretensions to literature, and furnished little more than his log-book as material for the volume to which his name is attached as author. A good many stories have been current in literary circles about changes in WOODWORTH's, manuscript, which were made in order to preserve an appearance of probability in ascribing the authorship to Capt. MORRELL. WOODWORTH, with a poet's impulse, had garnished the narrative with copious quotations from SHAKSPERE,—which were afterwards omitted as not being strictly in the line of the Captain's usual reading. 11

What did not get deleted in Morrell’s Four Voyages were the ghostwriter’s plagiarisms from other travel narratives, for example the long passage on the Lobos Islands off Peru, copied nearly verbatim from A Narrative of Voyages and Travels (Boston, 1817) by Amaso Delano. In 1852 Woodworth’s bold plagiarism of Delano elicited the complaint of a Boston editor about the unreliability of Morrell’s 1832 book.12 To which the New York Times replied, in effect, “No big deal.” However you take it, the 1852 exchange offers two good tokens of a ghostwritten narrative: over-quoting Shakespeare and plagiarizing (as Melville would soon do in “Benito Cereno”) Amasa Delano. A third token, over-imaginative personification of animals, was exposed in Josiah Gregg’s confessed “repugnance” for an overwrought section on prairie dogs invented by his first ghostwriter, Count Tasistro.13

In early editions of James Riley’s thrilling Narrative of shipwreck, capture and enslavement in Africa, the author frankly thanked Anthony Bleecker and John Shippey, Jr for helping him write it. In spite of Riley’s own public acknowledgement, later corroborated by Dr. Francis and other eminent authorities, Bleecker’s role as ghostwriter has been denied or minimized—unnecessarily, it seems to me—by several historians in the 21st century. Donald J. Ratcliffe, for example, in dismissing the well-informed testimony of Riley’s contemporaries, would appear to regard any substantive contributions by another writer as grounds for rejecting Riley’s claims to authorship, and for questioning his integrity. But that’s not how ghostwriting works. As Colonel Stone explained, explorers explore and writers write. Explorers may need writers to help them make readable books of their travels and adventures, but once a work is in print, the explorer gets to enjoy all the customary rights and benefits of authorship. In this view of things, we are bound to credit Captain Riley as the main actor and author of his 1817 Narrative. At the same time, we are also allowed to read sentimental effusions, imaginative metaphors, and poetical allusions like this echo of Book 1, Canto 11 in Spenser’s Faerie Queene

“Night had now spread her sable mantle over the face of nature….”

as tokens of ghostwriting dropped by another writer, this one by Anthony Bleecker.

To sum up, little of the stigma associated with ghostwritten works and their authorship was recognized in the 19th century, particularly in connection with published accounts of travels and voyages. By Melville’s time what we now call ghostwriting was regarded as

a legitimate branch of editing

a valuable service to literature and learning

an honorable way of bestowing or obtaining full credit for authorship

a useful means of reaching more readers; and

best practice in the genre of travel and exploration.

Now for some probable tokens of ghost-authorship in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” the 1851-3 series that debuted in the June 1851 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger.

Interjections

As previously discussed, the first token of ghost-authorship in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” is the direct address to the reader that begins the first installment.14

Oh reader! “gentle” or not,—I care not a whit—so you are honest….

To be sure, use of the grammatical second person by the narrating Captain of U. S. Dragoons is a stock literary device. That is pretty much the point. The handling of “Oh reader!” reveals an experienced writer at work. In this case it’s not merely the device itself, but also the changes rung—for example, the valuation of honesty over gentility—that indicate a writer with more than conventional literary designs.

More signs or “tokens” of ghost-writing may be found in the half-dozen interjections that pepper the June 1851 installment. Six writerly exclamations appear in the first installment. None is featured in letters or travel writing by Philip St. George Cooke, outside of material incorporated in Scenes and Adventures in the Army. Each is exemplified in the writings of Herman Melville—so well in some cases (oh ye and pshaw, for example) as to seem characteristic of his style. Listed below are specific instances of comparable interjections in Melville’s writings, comfortably employed. Usages in boldface occur in the June 1851 installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.”

Ah! if : Ah! if I could go forth like Zanoni…

Ah! if ever it lay in embryo like a green seed in a pod….

—Mardi Vol. 1 Chapter 89Ah, if man were wholly made in heaven, why catch we hell-glimpses?

—Pierre; Or, The AmbiguitiesAh, ah—if, now, that was, indeed, a secret sign…. —Benito Cereno

Behold! : Behold! the prairie…

Behold the organ! —Redburn: His First Voyage

Behold. Oh Starbuck! —Moby-Dick Chapter 132: The Symphony

Behold! —Cock-a-doodle-doo!

Behold morn’s rosy martyrdom! —Clarel Part 3 Canto 21, In Confidence

Oh! ye… : Oh! ye hypocrites—demagogues—

Oh! ye state-room sailors…. —Typee Chapter 1

Oh ye Tapparians —Mardi Volume 2 Chapter 26

oh ye! who think of cruising in men-of war —White-Jacket

Oh! ye whose dead lie buried beneath the green grass;

—Moby-Dick Chapter 7 The Chapel’Oh, ye foolish! —Moby-Dick Chapter 73

Oh, ye frozen heavens! —Moby-Dick Chapter 125

Oh! ye three unsurrendered spires of mine….

—Moby-Dick Chapter 135, The Chase—Third Day.“Drive, drive in your nails, oh ye waves!

Moby-Dick Chapter 135, The Chase—Third Day.“Oh, ye stony roofs, and seven-fold stony skies!” —Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities

pshaw! : Stevens’ new book, pshaw!

Shout not, nor exclaim, “Pshaw!” —Letter to John Murray, March 25, 1848

— Pshaw! you cry — & so cry I. — Letter to Evert A. Duyckinck, February 12, 1851

Pshaw! some one has fainted,—nothing more. —Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities

Soon, with some African word, equivalent to pshaw, he tossed the knot overboard. —Benito Cereno

True! : True! — you remind me though…

Uttered by most all the talkers in Mardi: and a Voyage Thither (1849):

“True! true!” responded the raving wife

“True, my lord,” said Babbalanja;

“Very true, Babbalanja”

“True,” said Mohi,

“Ah! how true!” cried the Warbler.

“Too true!” cried Yoomy.

“It is true, then,” said Media.

Well! : Well! — a pretty salamagundi I shall have of it.

Well, well, well! Stubb knows him best of all,

—Moby-Dick Chapter 108 : Ahab and the Carpenter.

Inverted word order

Another token of literary prowess, characteristic of poetry and fiction rather than narrative description, is inverted word order in the expressions “said he” and “thought I.” These instances occur in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border”:

“So,” said he….

“Friend,” thought I, “to obey orders is duty….”

“Oh Truth! thought I. How often wilt thou forsake the mighty….

Such usages occur frequently in Melville’s writings. These two are particularly well exemplified in Moby-Dick (1851) and Pierre (1852), works that Melville published during the time span of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” 1851-1853. Melville employs the locution thought I seven times in two consecutive chapters of Moby-Dick: four instances appear in Chapter 2 The Carpet-Bag, where Ishmael looks for lodging in New Bedford; and three in Chapter 3 where he finds it at The Spouter Inn.

Too expensive and jolly, again thought I —Chapter 2, The Carpet-Bag

Ha! thought I

Rather ominous in that particular connexion, thought I

True enough, thought I,

The devil fetch that harpooneer, thought I —Chapter 3, The Spouter Inn

And what is it, thought I, after all!

What’s all this fuss I have been making about, thought I to myself

Three more instances occur in Moby-Dick chapter 8: The Pulpit. And two more in Chapter 10: A Bosom Friend:

“I"ll try a pagan friend, thought I.”

But what is worship? thought I.

The first instance in Chapter 10 has the conjunction of friend with thought I, similarly instanced in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” (“Friend,” thought I).

Use of the phrase wilt thou in the apostrophe to “Truth” is well worth noticing, too, since this more-poetical-than-usual kind of talk will recur throughout the magazine series. Already in this first installment we find the narrator casually employing the second person familiar pronoun together with the appropriate verb conjugation, here thou (2nd person, subject form) + wilt (present tense, indicative mood), only reversing the usual order in English by placing the subject (thou) after the verb (wilt). Melville makes it “wilt thou” four times in Moby-Dick; and six times in Pierre; each instance of “wilt thou” in Pierre occurs in a question. (In declarative statements the expected order “thou wilt” occurs sixteen times in Pierre; five in Moby-Dick.)

Another such inversion, interrogatively expressed, is didst thou, as here:

“—how, bright star, didst thou get thy name?”

One comparable instance occurs in Moby-Dick Chapter 16: The Ship, when Captain Peleg interrogates Ishmael:

“Didst not rob thy last Captain, didst thou?”

Pierre contains five examples of the locution didst thou.

Demonstrably, then, the author of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” writes like Melville in the employment of

Interjections, particularly Ah! if and Oh! ye;

Elizabethan-style pronouns and verb inflections in the second person, plural ye for “you all” as well as singular thou (as subject) and thee (object) forms; and

Inverted word order, verb before subject as in “thought I” and “said he.”

Did Philip St. George Cooke elsewhere sound like the narrator of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border”? No, never that I have been able to find anywhere in his extant personal correspondence, military reports, and journals, except as inventively recast in the magazine and book versions of Scenes and Adventures in the Army. Of course I know that other writers besides Herman Melville employed these devices, too. Not Melville’s friend Hawthorne, though, whose 1851 House of the Seven Gables offered none of the parallels to be found in Moby-Dick. Dickens, for another example, did not write like that anywhere in the 1850 blockbuster, David Copperfield.

For a better sense of who (besides HM) actually would have used these particular words and constructions, I searched in HathiTrust Digital Library for all the interjections and grammatical constructions identified above in works published between 1820 and 1851. Answer: all hallmarks of the literary style exhibited in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” are shared also by Elizabethan dramatists, Romantic poets—Byron and Keats, of course, but also Mary Botham Howitt and L. E. L.,— and popular novelists, particularly Edward Bulwer-Lytton in, say The Caxtons: A Family Picture and the American genius John Neal in Logan, A Family History. I will gladly add Neal to the short list of ghost-authorship candidates to be considered in a later chapter, along with PSGC’s literary nephews Philip Pendleton Cooke and John Esten Cooke, Kentucky poet and social reformer Mattie Griffith, and Melville’s friend the poet and noted travel author Bayard Taylor.

Inferior-Superior motif, on the prairie

Melville wrote like they did in the book he was still fretting over but nearly ready to have printed and be done with, when “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” debuted in the June 1851 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger. Beyond the parallels of vocabulary and grammar cited above are interesting correspondences of theme and dramatic action or plot. Like Ishmael in the first chapter of Moby-Dick, the narrator in the first episode of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” displays an appealing sort of philosophical detachment while contemplating his predicament. Ishmael’s early concerns and conceits are itemized in the great essay by Harrison Hayford, “'Loomings': Yarns and Figures in the Fabric.”15 Broadly speaking, the first chapter of Moby-Dick as Hayford reads it introduces Ishmael as the “sympathetic but perplexed observer” while exemplifying the central and recurring motif of “confronting an insoluble problem.” Most relevant to my investigation here is Hayford’s analysis of how Ishmael accounts for “why he goes to sea as a common sailor.”16 In this category, as Hayford shows, the “leading and dominant” motif “is that of the inferior-superior relationship, involving the acceptance or rejection of imposed authority.”

Handled with similar detachment, the prairie version of Ishmael’s inferior-superior motif is artfully introduced at the start of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.” Of course, Philip St. George Cooke must have been concerned more or less constantly about matters of military rank and duty. He was ready and well able to discipline subordinates and defend his actions to superiors. What the real Cooke lacked, however, was something he could not afford to have as a cavalry officer in charge of 200 men, a loftier perspective on his decision-making gained through meditation and philosophical reflection. Somebody else, call him Cooke’s ghostwriter, has made the narrator a prairie Ishmael who will indulge in self-criticism of his own feelings and decisions, and counsel himself to embrace the virtue of submitting to authority.

One variety of the inferior-superior motif appears very early on, when the narrating Captain of U. S. Dragoons complains that he has no “equals” in rank and therefore no “social friends” with whom to converse. In this figuration the narrator casts himself as the lonely superior, isolated from human companionship like “a great Commodore / alone in the cabin of a seventy-four.” The Ishmaelian twist comes right after a direct quote introduced in the manner of fiction with inverted word order, “said he”:

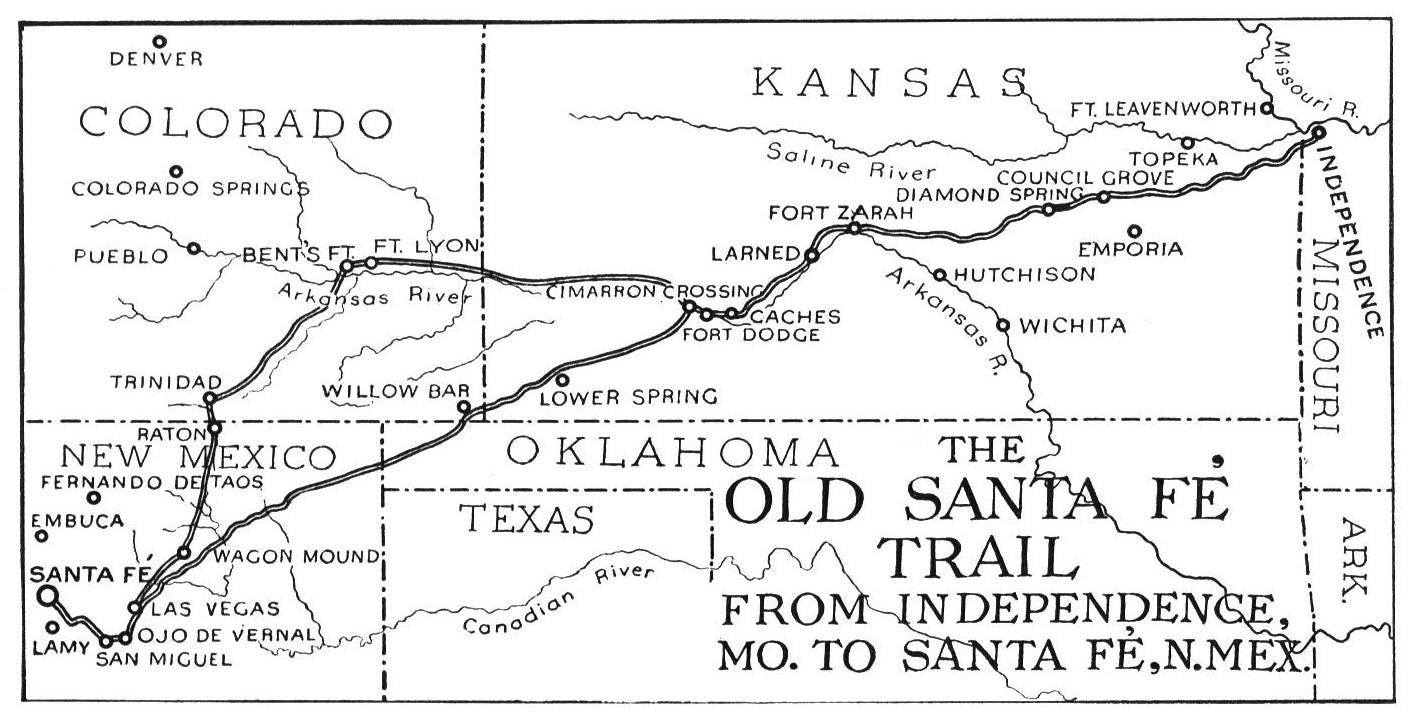

“So,” said he, “so there is not a bandit on the road; we are going for nothing….”

Although formally presented in the third person, the complaint would seem to be that of Philip St. George Cooke himself.17 I say that because these are the very sentiments that Cooke expressed with just a little less heat in his formal report of October 26, 1843 on the fall escort of Santa Fe traders. There Cooke was characteristically blunt, even when writing literally on the record to the Adjutant General. Mexican traders he regarded as “licensed smugglers”; the relatively few Americans involved in the Santa Fe trade were “nearly all adventurers, who live cheaply on buffalo, avoid the restraint of society, and at Santa Fe plunge into the dissipations of probably the most abandoned and dissolute community in North America.” In Cooke’s view, stated with his usual candor, the merchants only wanted protection from American desperadoes, not Indians. Being heavily taxed in New Mexico, “the trade is a disadvantageous one; there being no return profits; and the wagons return empty.” High tariffs, arbitrarily imposed, resulted in “overloaded wagons” and consequently more trouble for the U. S. Dragoons charged with escorting the heavily burdened and badly managed caravan.18

All that belongs to the official record. Unofficially, a saltier version of Cooke’s complaint is attributed in the June 1851 installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” to an anonymous interlocutor:

"So," said he, "so there is not a bandit on the road; we are going for nothing,—to wait on these ragged-rascal greasers. It will ruin the regiment! There has been expense enough for the trip already to break it down. I had rather be in the infantry."

Later, Cooke acknowledged the quoted words as his own—written, as he informed his nephew John Esten Cooke, in his tent on August 29, 1843 “after a hot hard day’s march.”19 As originally expressed in writing, Cooke’s tirade most likely would have been intended for private eyes only. Although its documentary source is unknown and presumably lost, the quoted outburst sounds to me like something once confided to his personal diary or correspondence, say a letter addressed to his wife. As framed by the narrator in the Southern Literary Messenger, however, Cooke’s overheated language signals “grumbling” by an inferior, complaining of indignities imposed by superiors.

Whereas the real Captain of U. S. Dragoons wrote in his tent, our prairie Ishmael situates himself in the shade, contentedly reading and thinking (during a heatwave, about heat) under a “fine oak” tree. The narrating “Captain” has thus adopted one of Melville’s favorite attitudes, that of a lounger in the shade. The progression of present participle verb forms is worthy of all the wanderers in Mardi as well as Ishmael, as the narrator pictures himself “reclining,” then “gazing,” and after that, “wondering” until

“the very idea of talking, then, was heating; so I only thought. “Friend,” thought I, “to obey orders is duty; and it is honorable to do duty. I would not undertake to think for my superiors if it distressed me so much.”

Jump-started by “thought I,” the interior monologue anticipates Ishmael’s thought process in Moby-Dick, particularly the chain of reasoning that will lead Christian Ishmael to worship with Pagan Queequeg.

But what is worship? thought I.… to do the will of God—that is worship. And what is the will of God?—to do to my fellow man what I would have my fellow man to do to me—that is the will of God. —Moby-Dick Chapter 10: A Bosom Friend

The first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” gives us Ishmael’s transitive logic, employed in a prairie exhibition of Ishmael’s most characteristic motif, as Hayford mapped it. Explicitly, the Captain’s reasoning invokes the inferior’s discomfort in relation to “superiors”:

“I would not undertake to think for my superiors if it distressed me so much.”

The opening act in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” thus showcases the defining feature of Moby-Dick according to Hayford, well worth repeating: “the inferior-superior relationship, involving the acceptance or rejection of imposed authority.”

As will be seen, compared with Cooke’s official report to the U. S. Army, the opening installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” looks and sounds like a highly imaginative rewrite. Reality-based, yet replete with fictional devices. And full to the brim of romance and poetry.

The imaginative fictions and poetical effusions in the magazine series that became Part II of Scenes and Adventures in the Army are hard to miss, and for that very reason have bothered readers consulting either version for reliable military history.20 Nevertheless, Philip St. George Cooke did overlook them. Either he missed the fictions entirely, or did not value them one whit. Writing to his nephew in Richmond, on May 15, 1851, Cooke pitched the first installment of the new series as a straightforward account of the second military escort of Santa Fe traders in 1843, copied “almost verbatim” from his private diary and correspondence.

Commentators before now have generally avoided the fictional elements, almost always evaluating the book version in Scenes and Adventures in the Army, Part II, without even knowing about the earlier publication of major portions of the narrative in the Southern Literary Messenger. Most notably, Otis Young in The West of Philip St. George Cooke (Arthur H. Clark Company, 1955) regarded the matter of 1843 in the second part of Scenes and Adventures in the Army as largely a transcript from Cooke’s private diary or journal. Young believed that both the official report of the second escort from August 24 to September 25, 1843, and the considerably embellished narrative of that expedition in Scenes and Adventures derived from a lost “diary.” Thus equating the published rewrite with a presumably lost diary, Young decided the relatively terse account housed in the National Archives with official Letters to the Adjutant General can best be “taken usually in alternate succession from Cooke’s original diary.” As Young has it, the diary-rewrite in this section of Scenes and Adventures in the Army plus the official army report together “make a very complete account of the autumn expedition.”21

In my view the effect of completeness may justly be appreciated as an illusion, achieved through skillful revision of Cooke’s detailed report of the previous expedition in the summer. More tokens of ghostwriting in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” will show what I mean.

As noted above, Philip St. George Cooke precisely dated his angry vent in a tent to August 29, 1843 “after a hot hard day’s march” west and south. By then Captain Cooke and company were about a hundred miles from Fort Leavenworth where they had departed on the 24th, still a couple of days away from Council Grove.

We are not told this yet in either the magazine or book versions, but Cooke had just been there in July, homeward bound to Fort Leavenworth. His journal record of the earlier military escort recounted three consecutive days—July 17, 18, and 19, 1843—of marching back through Kansas in extremely hot weather. Although narrator and troops are now supposed to be heading west again, late in August 1843, major details of the prairie setting in this opening installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” are borrowed not from Cooke’s lost “diary” of the fall march (which may well have existed, and gotten lost before it could be mined for source-material in 1851, either by Cooke himself or his literary ghost) but from entries for July 1843 in Cooke’s extant “Journal of the Santa Fe Trail.”

Poetically situated in a prairie desert, “a hundred miles from any place,” the action and invented dialogue with an “Imaginary Friend” ostensibly take place “in the dog days of 1843” after three exceptionally hot ones, “three of the hottest I have felt.” No more precise date is given anywhere in this first installment. The next, published in the September 1851 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger, begins with a supposed journal or diary entry dated “Sept. 1” which confirms the time frame as definitely that of the fall expedition. However, to the end of this narrative section (concluding the matter of 1843 in the January 1852 number) the highly imaginative rewrite will continue to borrow key details from Cooke’s account of the summer expedition. Here in the first episode, we already encounter a fusing or melding of descriptive details lifted from journal entries in July 1843 with the dramatic predicament of Captain Cooke in late August, when shifting circumstances forced him to choose between marching on to Santa Fe for (in his professional opinion) unnecessary protection of mostly Mexican traders aka “licensed smugglers” and their overloaded wagons, or going home.

Once revealed, this transposition of source material for aesthetic effect can be seen and perhaps better appreciated as the work of a talented ghostwriter or editor.

The following passage in the first installment of Scenes Beyond the Western Border

We are on a pretty hill near the spring and grove of a nameless tributary which meanders the beautiful valley of the Kansas river;—a hundred miles from any place; and it is in the dog days of 1843, and there have been three of the hottest I have felt; the unusually light breeze has been right behind, and only felt in bringing with us our dust. "Dog days." Oh Sirius, thou brightest and nearest sun;—the centre,—it may be of many a more happy planet, "more social and bright" than this;—how, bright star, didst thou get thy name?

is an expertly compressed re-write of these entries in Philip St. George Cooke’s 1843 Journal of the Santa Fe Trail:

I made a noon halt, & found the "110" nearer than I expected. I marched on about 3 miles to a small grove, a half mile north of the road. It was very hot today: I had the horses led some miles— a light air from the N. E. frequently blew the dust after us, so crooked was the road. The march 23 miles.

18th. July. Nothing was lost by turning out or coming through the hollow to the camp ground last night. It has rained around us; the white clouds have caught the wings of the wind, and all is still & sultry. We marched six hours without water, when at 1/2 past 12, we reached a small branch ahead, of "Rock Creek"; standing water was there found. After 2 hours rest the march was pursued; in 2 1/2 miles we passed a small cottonwood, marking a fine spring. 3 1/2 miles beyond I encamped at "Hickory grove," which marks surrounds a fountain which gushes from the hill side and purls its way, adorning & refreshing the fair Kanzas valley; this, now in its splendid maturity of foliage and grass, has gladdened our weary eyes as we marched along the winding hills. The march 25 miles.

July 19th. Another excessively hot day, with scarce any motion in the air...July 20th. The three sultry days as usual, brought a change: at dark last night, a sudden blast from the north came near prostrating every tent: it was followed by moderate showers.

There is no comparable entry documenting three consecutive days of extreme heat in Cooke’s official report of the second, shortened expedition from August 25 to October 25, 1843. Again, the opening scene of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” ostensibly set in late August 1843, appears to have been imaginatively recreated from Cooke’s written record of “three sultry days” in mid-July of the same year.

Five words borrowed in the rewrite of this July entry in Cooke’s 1843 journal

“… we passed a small cottonwood, marking a fine spring. 3 1/2 miles beyond I encamped at "Hickory grove," which marks surrounds a fountain which gushes from the hill side and purls its way, adorning & refreshing the fair Kanzas valley”

are hill, spring, grove, valley, and Kanzas = Kansas River. All five are kept in this compressed rendering of the opening scene:

“a pretty hill near the spring and grove of a nameless tributary which meanders the beautiful valley of the Kansas river.”

Significant revisions to the July 1843 text include the changing of “a fountain” that “gushes” and “purls” into “a nameless tributary” that “meanders.”

Also lifted from the July report (in addition to the three-day heatwave and setting in the Kansas River valley) is the dust kicked up by mounted dragoons on the march, and the light breeze that blew it their way again, from behind. In July the breeze came from the Northeast, the direction of their march back to Fort Leavenworth, but followed them anyway as they marched in zig-zag fashion on “crooked” paths:

a light air from the N. E. frequently blew the dust after us, so crooked was the road.

The rewrite avoids Cooke’s original references to wind direction and switchbacks, putting the “light” wind “right behind” (paraphrasing “after us”) and thus making it seem as hard in late August as it was in July for participants to march ahead of their own dust:

the unusually light breeze has been right behind, and only felt in bringing with us our dust.

Introducing a new verb, the re-telling in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” makes both the relentless heat and unhelpful breeze “felt,” drawing extra attention to the the difficult conditions as the dragoons experienced them, from their point of view.

Questioning Sirius

Another, more immediately visible token of ghostwriting appears in the added reference to and riffing on Sirius the dog star. No mention of Sirius, the “dog star” or “dog days” appears in Cooke’s 1843 “Journal of the Santa Fe Trail,” the main source for this part of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.” Or anywhere else in Cooke’s writings, so far as I know.

Sirius is one of Herman Melville’s favorite stars. Only Arcturus and Aldebran are more frequently referenced by name in Melville’s writings.22 Moreover, as trailblazing scholar and stargazer John M. J. Gretchko has discovered, Moby-Dick contains a long-overlooked allusion to Sirius in relation to the constellation Orion. In Chapter 81, Melville’s narrator Ishmael recounts how the three harpooneers Queequeg, Tashtego, and Daggoo, formed “a diagonal row” as they stood up and “simultaneously pointed their barbs” at a sick and wounded old whale, also hunted by a crew from the German whaler Jungfrau or “Virgin.” In the same chapter, Derick De Deer, captain of the Jungfrau, is scorned by mates of the Pequod as “an ungracious and ungrateful dog” and a “Dutch dogger.” As Gretchko reads the language and imagery of this carefully constructed scene in Moby-Dick Chapter 81, the three poised “barbs” in the hands of hunters configured “in a diagonal row” represent the three stars that form Orion’s belt and suggestively “point to the Dog Star, Sirius, in the constellation Canis Major, the Great Dog, which was sometimes called the Dog of Orion.”23

Triggered by the phrase “dog days,” the narrative excursus in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” begins with a direct address or apostrophe to Sirius, invoking the absent star as “thou brightest and nearest sun.” The speaker, ostensibly a Captain of U. S. Dragoons, goes on to admit the possible existence of life on other worlds than earth, and then wonders what the name Sirius means. He puts the question bluntly and a bit mischievously

“how, bright star, didst thou get thy name?”

but of course gets no answer from Sirius.

From there the digression continues with a brief anecdote and poem, both about a memorable Indian fighter—unnamed, but apparently General Henry Leavenworth. Who, allegedly, had determined to terrorize “every Indian from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains” and make them “tremble” at the sound of his name. Something about the grandiosity or brazen viciousness of this vow once inspired the narrator to compose an “impromptu” or improvised, occasional poem in the General’s honor. Sirius plainly is the “dog-star” mentioned in the second line of verse:

Immortal man, brave General _____ [! exclamation added in 1857 book version]

The dark’ling dog-star at thy birth [1857: darkling]

And comet glowed—portents of fame [1857: And fiery comet,—portents of fame—]

Gave warning that thy awful name,

Uttered in wrath in valley, plain [1857: valley plain]

In echo should the mountains gain,

To teach each man of Indian race

From river bank to mountain base

TO TREMBLE.

At first glance the adjective dark’ling might seem a little puzzling here, where “sparkling” would more obviously describe the brightest star in the night sky. It’s not likely a typo, however, since the revised version in Scenes and Adventures in the Army merely removed the apostrophe to spell the same word darkling, while substantively emending “comet glowed” in the next line to read “fiery comet.” For this one we need a good dictionary. With Webster in hand, we can take “darkling” to mean simply “being in the dark,” shining like Sirius in the darkness of a December night, the brightest star visible from earth.

Alternatively, even the exceptionally bright Dog Star might appear darkened or temporarily dimmed in the path of a “fiery comet” or meteor.

Published accounts of the 1783 Great Meteor incorporated eyewitness recollections of previous events including the extraordinary fireball in 1719 that “burst out in such refulgent splendour as to efface the stars.”24 Henry Leavenworth was born on December 10, 1783; the month and year of his birth may have suggested both of the two “portents of fame” cited in the untitled “impromptu”: 1) the dominating presence of Sirius glowing in the dark night sky; and 2) the Great Meteor of 1783, widely witnessed in Scotland and England and extensively discussed in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

However we interpret darkling here, the adjective remains “a poetical word” according to Webster’s 1845 American Dictionary of the English Language. The entry there for darkling specifically associates it with Milton. As in other abridged editions in the 19th century, the name Milton suffices to cross-reference the well known simile in Book III of Paradise Lost where the bard compares his habit of verse-making to the singing of a “wakeful Bird” at night. Being blind, so literally “in the dark” like the nightingale, Milton had to compose epic poetry

“… as the wakeful Bird

Sings darkling, and in shadiest Covert hid

Tunes her nocturnal Note.”

Earlier, and seemingly of out of nowhere, the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” proffered a verse couplet about a lonely Commodore in the cabin of a 74-gun ship-of-the-line or sailing warship. Now comes this longer “impromptu” using a thoroughly poetical word with famous echoes in Shakespeare, Milton, and Keats. It would almost seem that our narrator, “A Captain of U. S. Dragoons” (whoever he is, really), has been itching to write poetry. At any rate, as a poetical word by definition, strictly according to Webster, darkling makes for a great token of ghost-authorship. This token seems especially telling since Philip St. George Cooke wrote no poetry that we know of, outside of Scenes and Adventures in the Army and the magazine series on which the second half of that book is based, “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.” Melville wrote lots of poems after The Confidence-Man (1857) bombed. One, at least, features the word darkling: the manuscript poem The Cuban Pirate, posthumously published in Weeds & Wildings with Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings (Northwestern University Press, 2017).

The segue from Sirius to “impromptu” verses about the belligerent army General and his audacious vow discloses yet another token of ghostwriting in the formula “talking of the x” (some thing) + “reminds me of a y (person).” As here employed, the formula works to achieve a smooth transition from something to someone. In his everyday writing Philip St. George Cooke seldom employed any transitional device this skillfully or confidently. Melville uses the exact same device in his second book.

CAPTAIN OF U. S. DRAGOONS:

“Talking of the Dog Star, on the Santa Fe road, reminds me of a general, who…”

MELVILLE:

“Speaking of the Fa-Fa reminds me of a poor fellow, a sailor, whom I afterward….”

In Omoo Chapter 33 Melville makes it “Speaking of” instead of “Talking of,” but with the same meaning and effectiveness.

More signs of a professional writer or editor at work may be detected in the wording of the apostrophe to Sirius which betrays the author’s debts to sources other than Cooke’s 1843 “Journal of the Santa Fe Trail.” One of the borrowed bits is a quotation from Thomas Moore’s poem, They May Rail at this Life. Not only the direct quote (referencing the doubtful existence according to Moore of “some happier planet, / More social and bright” than earth) is significant, but also the deceptively casual, offhand manner of its appearance and absorption into a larger argument.

Most intriguing, and revealing, is the narrator’s interest in astronomy and the plurality of inhabited worlds, expressed at the beginning of his direct address to Sirius:

“Oh Sirius, thou brightest and nearest sun;—the centre,— it may be of many a more happy planet, “more social and bright” than this….”

This part has been adapted from some version of a supplementary note on “Fixed Stars” added to the American edition of John Pringle Nichol’s Views of the Architecture of the Heavens (New York: Dayton and Newman, 1842):

We do not see with the naked eye in either hemisphere more than 1000 of these stars , though they appear much more numerous, owing to the confused manner in which they are viewed. The number, as seen through a telescope, is infinite. The nearest and brightest is the star Sirius, estimated to be 32 billions of miles distant from the earth; so that it would require seven millions of years for a cannon ball to reach it, constantly flying with a rapidity equal to that which it would have on leaving the cannon. To the inhabitants of Sirius our sun appears as a star, and the planetary system revolving around it, of which the Earth is one, is unseen, as are those of Sirius by us. All the fixed stars are supposed to be centres, or suns, of complete planetary systems.25

Where the writer or ghost-writer found the passage on “Fixed Stars” is uncertain. One possible source, besides the original “Note” in Nichol, is the encyclopedic Guide to Knowledge, Or Repertory of Facts (New York, 1845) edited by Robert Sears, where the same article on “Fixed Stars” appears between entries on “The Crane” and “Language of Birds.26 Another possible source for the borrowed passage is Oliver Steele’s Albany Almanac for 1842. There the note on “Fixed Stars” appears after the usual calendar of months, in between reprinted matter “On the Culture of the Pie Plant” and “The Spirit Bird,” a story of nautical adventure from Tales of the Ocean and Essays for the Forecastle (Boston, 1841) by John Sherburne Sleeper, writing under the pseudonym of Hawser Martingale.

Sleeper’s 1841 tale “The Spirit Bird” related the sad fate of a sailor named Jim Thompson whose increasingly maniacal behavior is a mystery to his shipmates. Thompson is haunted and eventually driven to suicide by the ghost of his murdered father in the form of an other-worldly bird, something like the Albatross in Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Thompson’s ship is said to be “the good brig Nightingale” under command of one Nicodemus Melville. Herman Melville in 1841 was away on his whaling adventures in the South Seas, but I imagine the Gothic plot and surname of Captain Melville would have interested him if he ever got the chance to read “The Spirit Bird.” Author and newspaper editor John Sherburne Sleeper would later publish a very favorable review of Moby-Dick in the Boston Journal.27

As demonstrated above, the apostrophe to Sirius is clearly indebted to at least two published sources, Thomas Moore’s poem "They may Rail at this Life” and a passage from Nichol on the Fixed Stars. A third, less definite influence would seem to underlie the Captain’s unanswered query,

how, bright star, didst thou get thy name?

Why even ask that? As the stuff of much learned discussion by antiquarians and scholars, the origin of the name Sirius makes for a not-so-innocent question. Our questioner here got no reply from the absent and silent star, of course. Nevertheless, discoverable answers, or conjectures, existed in print. While opinions differed, the most eminent authorities generally agreed in taking Greek mythology as merely the starting point of their investigations. For one, Sir William Drummond:

Thus Osiris, Sirius, and Siris, are only Greek corruptions of words which had their origin in the Oriental languages.28

Thomas Maurice in the sixth chapter of The History of Hindostan credits “the Astronomers of Chaldea, India, Phoenicia, and Egypt” with prior knowledge of Sirius and major constellations, long before the Greeks had it.29

Alexander von Humboldt devotes several pages to Sirius in Cosmos: a sketch of a physical description of the universe, Volume 3 (London, 1851).30 In Humboldt’s footnotes the Prussian Egyptologist Richard Lepsius identified Sirius with Sothis, “the Egyptian name of Sirius.”

Then as now, many sources treated Sothis as the female personification of the Dog Star. Sothis (aka Sopdet) was anciently associated with the “heliacal rising” of Sirius around July 19th, right before sunrise. The Dog Star’s reappearance on or around that date in the predawn sky coincided with seasonal flooding of the Nile River. Sothis or Sopdet is frequently connected with the Egyptian goddess Isis, queen of Osiris. As explained by John Gardner Wilkinson, quoting Plutarch on Isis and Osiris, the soul of Isis was understood to have been

transferred after death to Sirius or the Dog-star, “which the Egyptians call Sothis.”* That she had the name of Isis-Sothis, and was supposed to represent Sirius, is perfectly true, as the sculptures themselves abundantly prove; and the heliacal rising of that star is represented on the ceiling of the Memnonium at Thebes, under the form and name of this Goddess…. 31

Seeking to know the origin of the name Sirius implies wanting to investigate ancient languages, histories, and myths for knowledge about the meaning of existence. The whole problem of the universe could be lurking just under the surface of the Captain’s suggestive question, “how, bright star, didst thou get thy name?” Quick as it is, the narrator’s probing at the start of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” is something like Ishmael’s digging in the Palace of Thermes section of Chapter 41 in Moby-Dick. There Ishmael finds a figure of “Ahab’s larger, darker, deeper part” in Roman ruins underneath the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris. Below the glorious Gothic mansion turned museum, on exhibit in the Palais de Thermes, stand fragments of more ancient sculpture that according to Melville’s narrator include the visible image of a “captive king” on a “broken throne.” Ishmael challenges the reader to find and question him.32

Wind ye down there, ye prouder, sadder souls! question that proud, sad king!

Talking astronomy rather than archaeology, but impelled by an Ishmaelian urge to question far-away figures of ancient grandeur, the narrating Captain of U. S. Dragoons dares to ask the Dog Star about the hidden history of its name.

Promiscuous apostrophe

Regarded as rhetorical device, the diversionary address to Sirius exemplifies a literary trick that Melville scholar Bryan Short terms promiscuous apostrophe. As Short observes, this promiscuous use of a classic figure of discourse is a notable feature of Melville’s style that occurs at the start of his first book:

The beginning of Typee displays another of Melville's techniques, what can be called promiscuous apostrophe. He begins by addressing the reader directly, fades into soliloquy, and in subsequent paragraphs addresses the rooster, another sailor, and the "poor old ship" itself. The impression created is of a voice ready to fix on any imaginable auditor.33

As we have seen, “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” begins the same way, by addressing the reader directly:

Oh reader! "gentle" or not,—I care not a whit,—so you are honest—I will tell you a secret. I write not to be read, and I swear never even to transcribe for your benefit, unless I change my mind. All I want is a good listener; I want to converse with you; and if you are absolutely dumb, why I will sometimes answer for you.34

But "Oh reader!" only makes one apostrophe—when does the narrative get promiscuous? Almost immediately. Here are nine more instances:

Oh, wide and flat,—shall I say "stale and unprofitable"—prairies! ...

Oh, gentle Herald [Mercury], that I could fly with thee!

Oh! ye hypocrites,—demagogues....

"Friend," thought I ....

Oh Truth!

Oh Sirius! thou brightest and nearest sun;

"Immortal man, brave General ———."

Oh Steam!

Imaginary Friend.— “But you were talking of books.”

All these addresses occur in quick succession. In the last example, the made-up traveling companion speaks for the first time. Unnamed as yet, he is referenced here in the first installment as “Imaginary Friend,” shortened to “I. F.” in the next. In the August 1852 installment we learn his name: “Frank.”

In his first speaking part, the invented companion interrupts just as the narrative begins to veer off topic when moving from the practical difficulties of book-publishing to the challenge of gardening in rocky soil. In terms of function, the Imaginary Friend’s first job is thus to keep the digressive narrator on track. In the interest of narrative coherence, the Friend might remind the narrator of the time, place, or subject at hand. To keep up the interest, the Friend will occasionally have to change the subject altogether, or at least try to. A perfect, early example of intervening to change the subject matter will happen very soon, when the Imaginary Friend invites the narrator for a stroll on the prairie. The first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” will close with a nature walk. And more talk.

Before that can get underway, however, the prod to keep talking about books yields more tokens of ghostwriting. One such token is “pshaw!” already counted above with similarly literary interjections. Also remarkable is the transparent and self-conscious presentation of the journey itself as an exercise in book-making. Having left behind his favorite works of non-fiction, the narrator determines to turn his empty journal into a book of dialogues with his (admittedly “Imaginary” = made-up, invented, fictional) traveling companion, the goal being “to fill up with our conversations this blank bound ‘book.’”

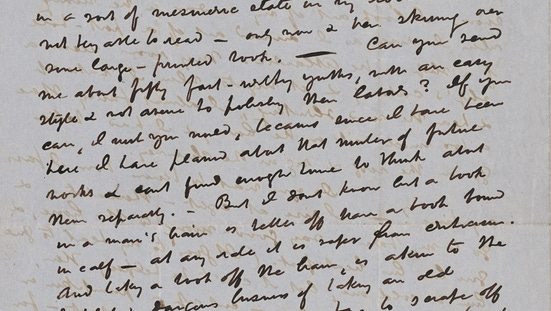

On the record, Philip St. George Cooke wished he could have furnished the U. S. Army with a more elegant version of his 1843 journal. As he explained in a postscript when submitting a copy to R. Jones the Adjutant General in Washington, he had found it a real chore merely to get the thing transcribed. Amid numerous “fatigues” and “press of more important duties” Cooke finally had to make the copy himself, failing to find any soldier who could read his bad handwriting:

Note: This Journal was kept in the midst of fatigues, & often a press of more important duties. It has been hastily copied under very similar circumstances. (I found a clerk could not decypher it). Thus it may prove a mere faithful picture of daily impressions; but it lacks the labor & polish, which I would willingly have given to it.” 35

Making his work legible was a major problem of writing that the real Captain of U. S. Dragoons shared with Herman Melville. Cooke relied on Army clerks to decipher his scrawls, if and when they could; Melville was routinely assisted in the same task by his wife and sisters. As a professional writer Melville himself made improvements in revision that Cooke seldom had the time to accomplish. In Cooke’s view it may not have mattered who did the “editing” of his written work, so long as the person hired was experienced and competent. The desired literary polish could be added later by any qualified solider-ghostwriter under his command. Without, he may have assumed, materially affecting the substance of his original compositions.

Irving’s riverine writings

The next discernible tokens of ghostwriting involve an eloquent tribute to the most distinguished and successful American writer of the time, Washington Irving:

They have spared Irving, his writings, flowing through broad margins of letter press; to what can we compare them, but to a crystal streamlet purling through flowery savannahs and sweet shady groves; and anon delving into cave-like clefts,—romantic recesses, where, of old, the fairies sought shelter from the glare of day.

This passage was revised in the 1857 book version to develop the metaphor of text-as-river even further by changing “writings” to “liquid sentences” and “broad margins of letter press” to “glittering margins of fairest typography.”

With or without later embellishments such as “liquid sentences,” the basic word-stream metaphor may reasonably be taken as a token of professional ghostwriting. As a rule, Philip St. George Cooke deployed figurative language rarely. Not counting cliches, you have to look hard to find a single simile, metaphor or any figure of speech anywhere in his everyday writing, whether about official Army business or in correspondence with friends and family members.

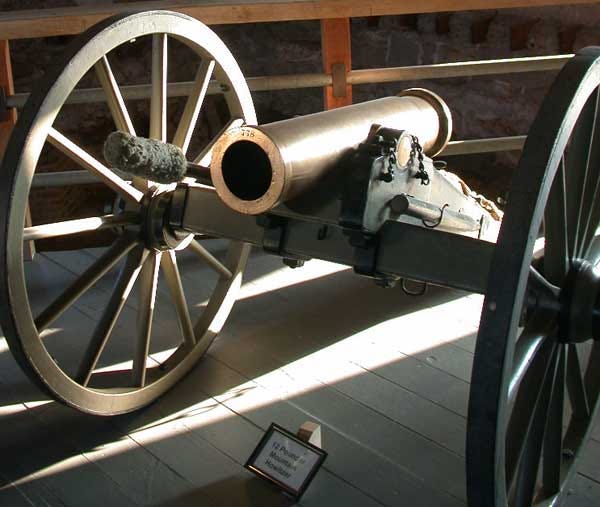

Cooke’s one reference to Irving outside of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” / Scenes and Adventures in the Army is perfunctory, like most of his literary allusions. It appears in the entry dated June 28th, introducing the story of what Cooke regarded as a uniquely “thrilling” event, hunting buffalo with a 12-pound howitzer:

Such is an abstract of the day's progress: the pen of an Irving might fail to paint the interesting sights, or to convey an idea of thrilling interest and excitement of a scene which all witnessed.36

However hackneyed, “pen of an Irving” does qualify as a bona fide literary term, being an instance of metonymy. Some particular thing associated with authorship, here the instrument that a famous writer uses to write with, stands more generally for great ability and success in the field of descriptive writing. To be sure, the expression “the _____ of a/an _____” was a sort of formula and commonplace in the 19th century.

As employed by Cooke in his 1843 journal, the formula was less than flattering to the cited author. Writing up his own unique experience of using an artillery weapon to slaughter buffalo on the prairie, Cooke doubted that even so great a prose stylist as Washington Irving would be able to adequately portray the novelty and excitement of the event. Cooke’s invocation of Irving in 1843 thus served to justify his own attempt, the production of a self-professed amateur.

Notwithstanding his appended note of apology for the overall lack of literary polish, Cooke treasured this particular section in his 1843 “Journal of the Santa Fe Trail.” We can tell that Cooke loved it as written, because decades later he succeeded in getting his original account published with minimal changes under the title, “An American ‘Bull Fight.’”37 This and another intensely dramatic event of 1843, the disarming of Texan freebooters led by Jacob Snively, were barely mentioned in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.”38 Neglect of both episodes resulted largely from the decision to focus on the abortive fall expedition instead of the more eventful summer march.39

Seemingly left to his own devices in the 1880’s, without the services of an imaginative “editor” or ghostwriter, Philip St. George Cooke gave long passages verbatim from his 1843 journal. More will be said in another chapter about later allusions in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” to the odd tragicomedy of Cooke’s buffalo hunt in June. What I want to highlight here is the choice Cooke made to leave out the passing reference to Washington Irving when quoting extensively from his own manuscript account. Though lavishly praised in 1851, Irving in 1882 proved dispensable.

On view here are the relative values that the real Philip St. George Cooke attached to fact vs. fiction. For Cooke, reality trumped romance every time. His forte as a writer was the faithful recording of day-to-day observations along with pertinent if often unsolicited commentary. Miles traveled, pertinent weather data, locations of campsites, availability of wood and water, descriptions of terrain and natural scenery, flora and fauna, the condition of men and beasts. Cooke was highly competent in his field which was observing and recording plain facts of day-to-day experiences. With very little editorial help he could describe everyday realities of military life perfectly well. However, to convey anything like “Romance,” he needed help. Considering the ultimate non-importance of Irving to Cooke except as shorthand for “generic successful author,” the overwrought text-as-river metaphor in the June 1851 encomium to Washington Irving may be taken as a great token of ghostwriting.

In the employment of elaborate riverine figures to describe words on a page, the narrative style of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” anticipates that of Melville in his next novel:

It was a little curious and rather sardonically diverting, to compare these masterly, yet not wholly successful, and indeterminate tactics of the accomplished Glen, with the unfaltering stream of Beloved Pierres, which not only flowed along the top margin of all his earlier letters, but here and there, from their subterranean channel, flashed out in bright intervals, through all the succeeding lines. 40

As in the Captain’s fulsome and fanciful prairie tribute to Irving, Melville in Pierre exploits the double sense of "margin" as space on a page and as the edge or bank of a river. Not only that, Melville (in what for him is a characteristic image) pictures the word-stream flowing underground, through a "subterranean channel" of text, but periodically resurfacing at "bright intervals." Just so does the Irving tribute in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” picture the text-river as intermittently hidden, flowing down, underground, "anon delving into cave-like clefts,—romantic recesses" below the visible surface.41

For the image of writing as a river in Melville’s personal correspondence, compare also his letter of Tuesday, July 22, 1851 to Nathaniel Hawthorne:

“I thank you for your easy-flowing long letter (received yesterday), which flowed through me, and refreshed all my meadows, as the Housatonic—opposite me—does in reality.” 42

Published just one month before, the opening installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” found the narrator in a similar mood, visualizing Irving's fine writing as a river of text "flowing through broad margins" like "a crystal streamlet purling through shady groves." Book margins have become banks of the textual river. To illustrate the beautiful and natural fluidity of Irving's prose, the Captain quotes from memory a sentence in Knickerbocker's History of New York. Here again is the passage as it originally appeared in the June 1851 installment of Scenes Beyond the Western Border:

They have spared Irving, his writings, flowing through broad margins of letter press; to what can we compare them, but to a crystal streamlet purling through flowery savannahs and sweet shady groves; and anon delving into cave-like clefts,—romantic recesses, where, of old, the fairies sought shelter from the glare of day. "And the smooth surface of the Bay presented a polished mirror in which Nature saw herself and smiled." Were I an eastern monarch,—who had stuffed the mouths of poets with sugar and gold—how could I have rewarded such a writer?

The Captain's admiring quotation from Irving is only slightly off. In Diedrich Knickerbocker's History of New York (1809) the temporarily peaceful scene is New York Harbor, pictured during the narrator's stroll on The Battery where

“the waveless bosom of the bay presented a polished mirror, in which nature beheld herself and smiled!”

Quoting from memory, Cooke (or more likely his ghostwriter) literalized Irving’s original figure, making the placid water a “smooth surface” in place of Irving’s “waveless bosom.43

Rewarding writers like an Eastern monarch

Another rhetorical flourish in the tribute to Irving, on top of and distinct from the main word-stream conceit, is the narrator’s hypothetical identification with “an eastern monarch” as a patron of literature. For no good reason except perhaps the whim of a ghostwriter, the narrating Captain of U. S. Dragoons has alluded to what another nineteenth-century travel writer described as “the Persian custom of stuffing the mouths of poets with sugar-candy.”44 More specifically, this extra helping of orientalist embellishment recalls The Adventures of Hajji Baba, of Ispahan (London, 1824) by James Justinian Morier.45 Details might have been borrowed directly from the first two volumes of Morier’s work, or indirectly from the useful and entertaining summary by George Paxton:

“A curious way of rewarding a courtier, or indeed any one who has rendered agreeable service to a prince or great man, obtains in the East, particularly in Persia, where it is very common, and that is, filling his mouth with sweatmeats, or with gold as much as it will contain. 'Go to the poet,' says the king, in an entertaining scene of Hajji Baba, 'go kiss him on the mouth, and when that is done, fill it with sugar-candy;' upon which, the noble of nobles approached the poet, gave him a kiss, and then, from a plate of sugar-candy, which was handed to him, he took as many lumps as would quite fill his jaws, and inserted them with his fingers, with all due form. On another occasion, when the same bard delivered an impromptu in honour of the shah, he is represented as receiving the highest honour which can be conferred on a poet,—that of having his mouth filled with gold coins in the presence of the whole court.” 46

Before his tribute to Irving in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” Philip St. George Cooke had never appealed to any “eastern monarch” for any reason. Herman Melville had. Melville’s White-Jacket (1850) offers a parallel usage of the expression “eastern monarch” in chapter 91, where “Lemsford, the poet of the gun-deck” justifies his vow to renounce ocean travel by citing the historical example of one particular “Eastern monarch”:

“Profane not the holy element!” said Lemsford, the poet of the gun-deck, leaning over a cannon. “Know ye not, man-of-war’s-men! that by the Parthian magi the ocean was held sacred? Did not Tiridates, the Eastern monarch, take an immense land circuit to avoid desecrating the Mediterranean, in order to reach his imperial master, Nero, and do homage for his crown?”47

Whatever we make of the tribute to Irving in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” the narrator’s digressive identification with an “Eastern monarch” for the hypothetical purpose of rewarding a great American writer with the western equivalent of sugar-candy and gold-pieces, as the Shah of Persia rewarded poets in the tales of Hajji Baba, can safely be counted as another token of ghostwriting.

Multiplying books by hand

As we have seen, the opening installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” first engages the reader with a direct address from the narrator, ostensibly “A Captain of U. S. Dragoons.” All he wants is a good listener. Before we can decide if that would be us or not, the narrator’s one ideally honest and sympathetic reader gets turned into a fictional character named “Imaginary Friend.” The scene is set in Kansas during the oppressively hot dog days of 1843, interweaving actual details from the summer and fall marches described by Philip St. George Cooke in his official 1843 “Journal of the Santa Fe Trail.” The plot that belatedly emerges is based on Cooke’s real quandary near the end of August: return to Fort Leavenworth or proceed as ordered with the ill-advised escort of traders to Santa Fe? Cooke’s interesting real-life predicament generates questions of duty and obedience to superiors that the narrator entertains philosophically and theoretically, in thought only, while lounging in the shade “of a fine oak.” Early digressions include “impromptu” bursts of poetry, a loaded apostrophe to Sirius, and a lament over the decline of fine literature as “the Republic of Letters” falls to “a rank Democracy” of mass-produced trash.

From the jump, the narrator of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” shows himself to be oddly preoccupied with the making of books and literary reputation. His obsessive yet extremely self-aware wrestling with problems of writing, both practical and aesthetic, will continue throughout the series. Early on, and with little offered in the way of introduction or explanation, the narrator weighs the pros and cons of even attempting to publish a book. Something ambitious army officers presumably like himself should never do, since the very “idea of publishing a book is terrible; no military reputation could stand it.” Merited distinction, he reasons, is all but impossible to attain in the literary marketplace where

“not one in a thousand can venture in the guise of the ‘cheap literature’ of the day, unless, indeed, it be a newspaper extra (subscribed for in advance).”

Nonetheless, the narrating “Captain of U. S. Dragoons” might be willing to let a friendly editor arrange his “unamended scribblings” for publication, ideally if superintended “by an artist of the press” who duly values “fair wide margins and pictorial embellishment.”

Irving is the Captain’s model, not only for the beauty of his fluid prose, but also for the luxurious manner of its presentation by printers and book-makers, “flowing through broad margins of letter press” on the finest paper in fairest typography. In this view, Irving’s legacy as a great American author has been “spared” along with the actual, physical books that contain his writings, in consequence of their not being vended as “cheap literature” in the plainest “brown paper style.”

Were I an eastern monarch,—who had stuffed the mouths of poets with sugar and gold—how could I have rewarded such a writer?

The narrator’s passing fancy of being “an Eastern monarch” who routinely rewards great writers with candy and cash, leads directly into the following curiously worded conception of patronage, hypothetically extended by rich English capitalists:

Could all the private wealth of England, could all the hands of Birmingham and Manchester multiply the "Last of the Barons," for instance as in the days of the polished and literary Greeks,—in manuscript—to equal one week's supply! Published in London—and in two months a wanderer in the Rocky Mountains will pass the sultry noon, poring over its pages! Oh! Steam!—

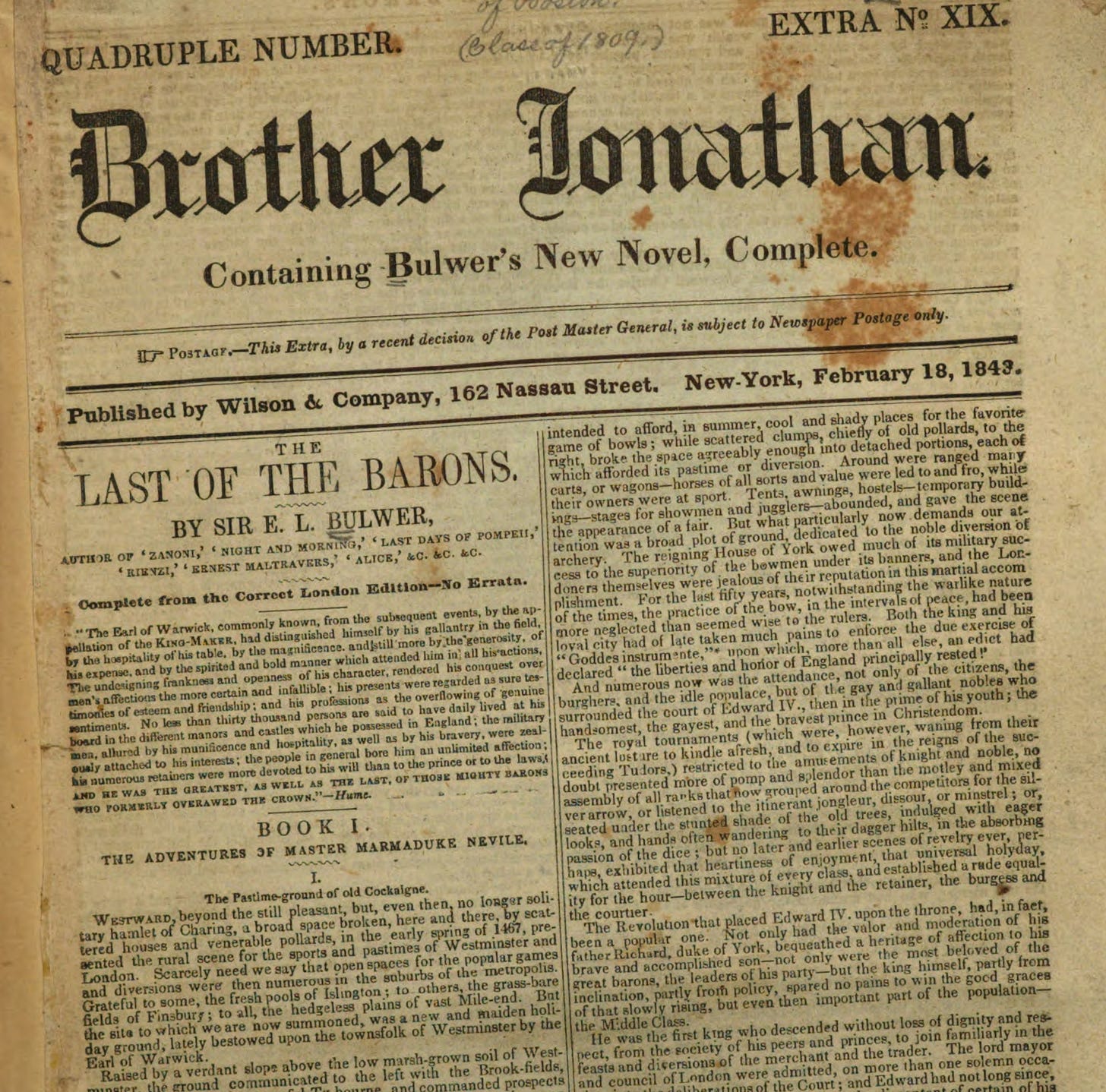

As hypothetically proposed by the narrator in the June 1851 installment of Scenes Beyond the Western Border, English factory workers in the industrial cities of Birmingham and Manchester could be employed to manufacture or "multiply" The Last of the Barons, the 1843 novel by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton. By multiply the narrator explicitly means “in manuscript,” copying it out by hand the way that scribes in ancient Greece transmitted manuscripts of classic literary and philosophical texts.

Evidently he imagines these famously skilled factory “hands” making elegant handwritten copies of Bulwer’s new novel in manuscript, the way publishing used to be done in pre-modern times before the invention of the printing press. At best, turning out copy after copy of Last of the Barons in the old fashioned way, the most industrious English workers might be able to reproduce "one week's supply" of books in manuscript.

The point of this conceit is to emphasize, by contrast, the incredibly rapid production and mass circulation of popular novels by means of the modern steam-powered printing press. In effect, the quaint notion of employing factory “hands” to “multiply” a guaranteed best-seller like Last of the Barons old fashioned way, “in manuscript,” serves to illustrate the staggering increase in productive capacity enabled by modern technology.

The Harpers published the American edition of Bulwer-Lytton’s historical romance The Last of the Barons on Friday, February 17, 1843, inexpensively priced at 25 cents in their popular Library of Select Novels. Even cheaper newspaper versions were available the next day in “Extra” editions of The New World and Brother Jonathan.

By Monday Bulwer’s new novel was “already in the hands of thousands” according to the Brooklyn Eagle of February 20, 1843. It needs no great stretch then to believe with the narrator of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” that in just a few months, “a wanderer in the Rocky Mountains will pass the sultry noon, poring over its pages.”