All I want is a good listener

Writing, talking, and rewriting like Herman Melville in "Scenes Beyond the Western Border" (1851-1853). No. 1, Introduction.

Oh reader! "gentle" or not,—I care not a whit,—so you are honest—I will tell you a secret. I write not to be read, and I swear never even to transcribe for your benefit unless I change my mind. All I want is a good listener; I want to converse with you; and if you are absolutely dumb, why I will sometimes answer for you.

Thus begins the first installment of “Scenes beyond the Western Border,” a mostly forgotten magazine series of military adventure, ostensibly WRITTEN ON “THE PRAIRIE” / BY A CAPTAIN OF U. S. DRAGOONS and intermittently published from June 1851 to August 1853 in the Southern Literary Messenger. Link below to Volume 17 via Google Books with the above-quoted intro on page 372:

https://books.google.com/books?id=61IFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA372&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

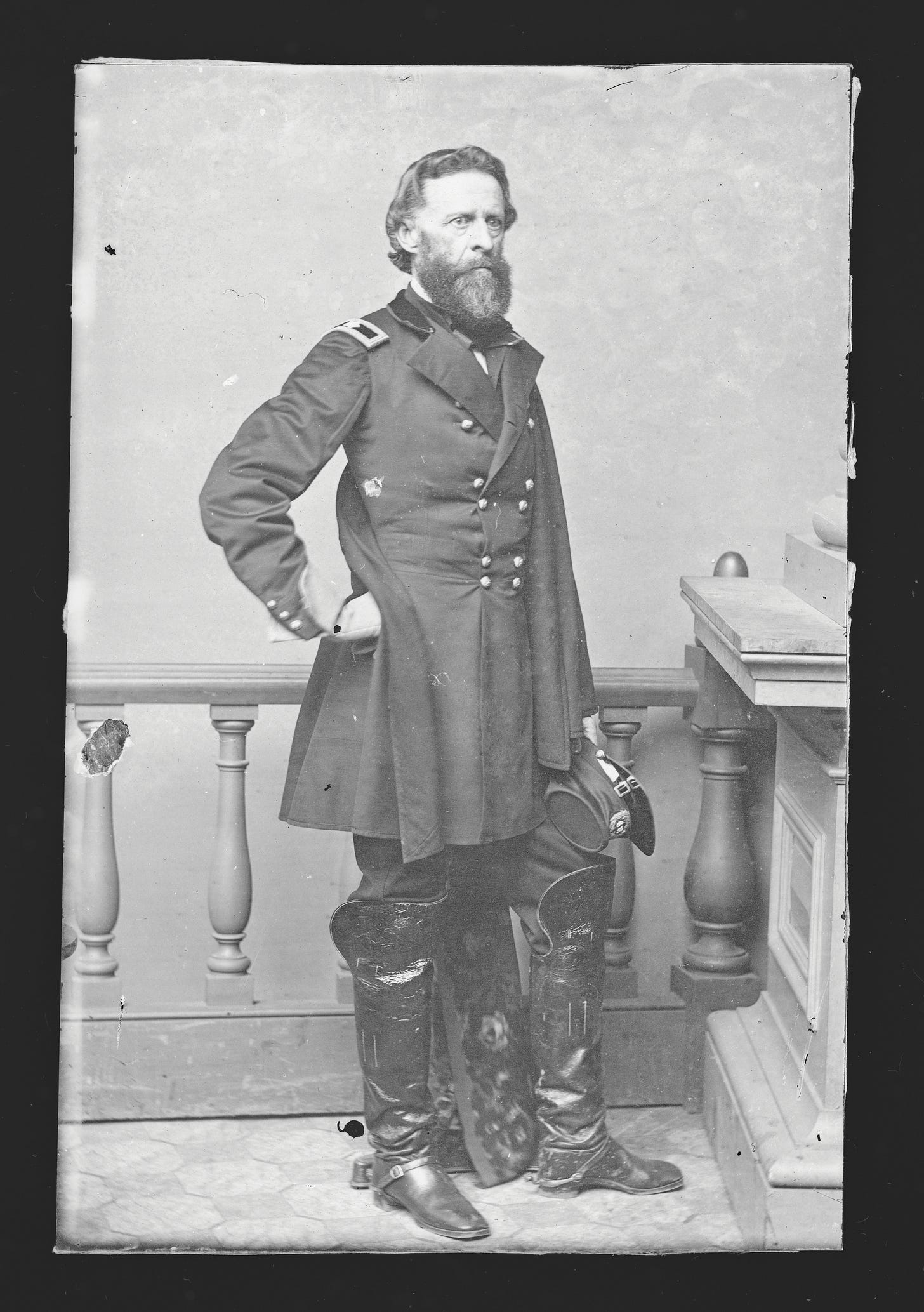

With interesting revisions, the thirteen installments of “Scenes beyond the Western Border” (1851-1853) later became Part II of Scenes and Adventures in the Army (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1857) by veteran cavalry officer Philip St. George Cooke.

Image Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Frederick Hill Meserve Collection. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.81.M3885

Part I of the 1857 book reproduces an earlier series, published 1842-1843 in the Southern Literary Messenger under the title, “Scenes and Adventures in the Army, Sketches of Indians, and Life Beyond the Border.” This prior series in the Southern Literary Messenger had been repackaged from even earlier pieces in different venues including the Army and Navy Chronicle. In February 1840 the first of four western sketches entitled Leaves from my Note-Book appeared in the Army and Navy Chronicle over the signature of "Z." Starting on June 18, 1840 these loose notebook “Leaves” by "Z." were extended in the same journal by Notes and Reminiscences of an Officer of the Army, a new series of military adventures signed "F. R. D." for First Regiment Dragoons. A couple of Indian romances and the racy tale of Hugh Glass filled out the 1842-3 series in the Southern Literary Messenger. These interpolated sketches originated in the St. Louis Beacon where they had appeared in late 1830 and early 1831 over the pseudonym, “Borderer.”1

The alluring subtitle of the book version represents the collection of these entertaining but episodic accounts, all previously published in magazines and newspapers, as a generically unified Romance of Military Life. As I discovered in microfilmed correspondence of John Pendleton Kennedy, Romance in the subtitle replaced the term Fragments in the working title for Cooke’s book project, “Fragments of a Military Life.”2 To be sure, the fragment was a staple of romantic poetry and prose fiction.3 As exemplified in Melville’s Byronic “Fragments from a Writing Desk,” the form admits, indeed boasts of incompleteness. While perfectly suited to a group of miscellaneous sketches, the Fragments tag might have discouraged a potential reader looking for coherence in a serious work of military autobiography. Three houses including Harper & Brothers respectfully declined the offer of “Fragments of a Military Life.” In the end, Cooke and his Philadelphia publisher went with Romance as the more enticing descriptor. Nevertheless, the first and arguably more accurate label for the travel narratives, military adventures, Indian romances, and philosophical prairie dialogues cobbled together in the book version of Scenes and Adventures in the Army was Fragments.

“Scenes Beyond the Western Border” (the later, 1851-1853 series that comprises Part II of Scenes and Adventures in the Army) chronicles two different expeditions of U. S. Dragoons: the military escort of traders along the Santa Fe Trail in 1843; and the 1845 Kearny expedition to the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains.4 Although based on first-hand accounts by Cooke and other participants, the narratives are later rewrites of earlier material that artfully re-create and enhance the impression of being “on the prairie” for real. What gives the game away are the invented prairie dialogues. Throughout, more straightforward descriptions of action and scenery provoke dialogues between the narrating “Captain of U. S. Dragoons” and the “Imaginary Friend” supposed to accompany him. Captain and Friend talk talk talk on diverse subjects from the fields of literature, history, science, philosophy, art, and religion. As we will see, a regular feature of these conversations is the running commentary on problems of writing.

At its most meta, a good deal of the prairie talk turns on criticism of the narrative-in-progress. Meta-fictional critiques are usually initiated by the narrator’s Imaginary Friend who tends to favor a plain, matter-of fact style of narration over the Captain’s more romantic and poetical flights of fancy. The style and substance of these recurring dialogues are amazingly Melvillean, as I will begin to show here and elaborate in subsequent numbers, hopefully.

For a start, let’s return to the June 1851 installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” and see how the “Captain” employs a convention of sentimental fiction and other kinds of popular writing by addressing the reader directly—in the second person, grammatically speaking:

Oh reader!

The self-conscious deployment of a stock literary device delays the narrative of far-western travel promised in the title. “Oh reader!” Who talks like that? In real life, nobody. Only writers, dramatically pretending to speak out loud to some imagined second person called “you.” Writers! Herman Melville, for one, chose to open his first book Typee (1846) with, as Mary K. Bercaw Edwards has observed, “an oral address to the reader”:5

Six months at sea! Yes, reader, as I live, six months out of sight of land….

—Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)

Another such address to the reader, closer in wording and dramatic intensity to the one that opens “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” appeared near the end of Melville’s third book:

Oh, reader, list! I’ve chartless voyaged. —Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849)

Not that I mean to offer parallel uses of the moldy “Oh, reader” convention as persuasive evidence of authorship. Experts agree, authorship is seldom or never proved by piling up verbal correspondences—even better, fresher ones than OH, READER. How about ghost-authorship? Or, to put it less contentiously, the possibility of ghost-authorship? Theoretically speaking, I mean. In principle, unwonted facility with literary devices might reasonably be taken for a sign of help from someone other than the putative author. Owen Chase’s Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex, for example, “bears obvious tokens of having been written for him” according to one expert in the art of ghostwriting.6

Obvious or not, “Oh, reader” might in this light be regarded as the first of many discernible “tokens” that “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” could have been professionally re-written for Philip St. George Cooke.

About the Mardi example I will venture to observe that numerous critical comments on Melville's "Oh, reader" apply equally well to the expostulation of our Captain of U. S. Dragoons here. Going all the way back to F. O. Matthiessen, who remarked in 1941 how Melville’s exclamatory address to the reader late in Mardi “strikes the note of intensity that became habitual with Melville in his pursuit of truth.”7 The intensity that marks Melville’s “habitual” truth-seeking famously radiates in writings from 1850-1852, the time of Melville’s encounter and close friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne. Examples abound in Melville’s pseudonymous review essay Hawthorne and His Mosses (ostensibly BY A VIRGINIAN SPENDING JULY IN VERMONT); in the enthusiastic “love letters” he wrote to Hawthorne after they became neighbors in Berkshire County, MA; and two books written under Hawthorne’s bewitchment, Moby-Dick (1851) and Pierre (1852).

Consider the timing, if you please. Unsolicited, unheralded, “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” debuted in June 1851, seemingly out of the blue. From his military post at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania, Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke (PSGC hereafter) had only mailed the brief first installment to the Southern Literary Messenger on May 15, 1851, care of John Esten Cooke in Richmond, Virginia.8 Unsure of its acceptance, PSGC expected his nephew would be surprised at the trial offering of a new series based on old adventures in 1843, eight years before. More on all that later. Now it’s about the chronology. Demonstrably (just you wait!), the unexpected submission from Carlisle Barracks in the middle of May 1851 was not a cleaned-up and polished version of Cooke’s 1843 army journal in manuscript, but a highly creative and skillfully managed rewrite. The rewrite seems recent, even a bit rushed in light of Cooke’s request for editorial help with the correct wording of a quotation from the scenic view of the Battery in Irving's History of New York. If recently produced, the test-piece that began “Oh, reader!” might have been composed in April or early May 1851. Written, that is, in the wake of Melville’s entertainment of Hawthorne at Arrowhead in March 1851, highlighted by their “smoking and talking metaphysics in the barn.”9 Their conversations would have made a great book—a la Thoreau, Hawthorne reportedly joked. All that summer Melville craved more of the same "ontological heroics," preferably lubricated with brandy or gin.10 He got what he wanted at Hawthorne's place in Lenox, as Hawthorne recorded August 1, 1851 (apparently without knowing it was Melville's 32nd birthday):

Melville and I had a talk about time and eternity, things of this world and of the next, and books, and publishers, and all possible and impossible matters, that lasted pretty deep into the night.11

As tended to happen around the invitingly quiet Hawthorne, the other guy did most of the talking. To one ear-witness Melville’s spoken words sounded like waves crashing into a rocky shore. Nathaniel’s wife Sophia Hawthorne heard and felt the tide of Melville’s talk during his daytime visits and memorably captured its oceanic urgency:

Nothing pleases me better than to sit & hear this growing man dash his tumultuous waves of thought up against Mr Hawthorne's great, genial, comprehending silences.12

For his part, Melville was glad to do the talking. And said so. Aware of Hawthorne’s renowned reticences, Melville maximized the appeal of their continued friendship, by taking full responsibility for performing whatever social duties might be required to keep it up:

“Don’t trouble yourself, though, about writing; and don’t trouble yourself about visiting; and when you do visit, don’t trouble yourself about talking. I will do all the writing and visiting and talking myself.” Letter to Hawthorne, early May? 1851.13

No pressure! Should Hawthorne deign to make another visit, Melville would do all the talking himself. This Melville assured Nathaniel Hawthorne, personally, in May of 1851. That it was typical of Melville to do so appears vividly verified by Sophia Hawthorne in that aforementioned letter of May 7, 1851 to sister Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. In June nearly the same promise (qualified by “sometimes”) would be made in print by “A Captain of U. S. Dragoons” in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border”:

“… and if you are absolutely dumb, why I will sometimes answer for you.”

The Captain desires companionship with a silent type like Hawthorne.14 All he wants is a good listener. In Hawthorne, as Leon Howard has it, "Melville found a good listener to whom he could talk philosophy, literature, or adventure without reserve."15

Hold up, wasn’t Melville busy enough with writing his blasphemous masterpiece? No. By late March, family members including his sister and chief copyist Augusta Melville thought “The White Whale” (first published in England as The Whale, in America as Moby-Dick) was already done. Revealed in a letter that Augusta received from her friend Mary Blatchford, as Hershel Parker explains.16 The White Whale book was not really finished, but Melville took a break and let Augusta go to recuperate at the Van Rensselaer “Manor House” in Albany.17

The plan, partly glimpsed in Melville’s known letters to Hawthorne, was for Melville himself to superintend the stereotyping by Robert Craighead in New York City. Melville figured to finish writing it there, on the 3rd floor of Craighead's book-printing office at 112 Fulton Street, prodded by the printer's devil.18 As Hershel Parker discovered in Augusta's letter to Allan Melville dated May 16, 1851, Herman had just seen brother Allan, briefly, on a "flying trip" to NYC.19 A "longer visit" was already scheduled. In June, insufferable heat and delays at Craighead's sent Melville back to Berkshire, as Melville informed Hawthorne on June 29th, with the great Whale book "only half through the press." A month after that Melville was finally done with the writing of it.

So there were breaks enough, and multiple delays. Some, ironically, motivated by the author’s infatuation with the esteemed dedicatee of Moby-Dick. Back in January Melville had used a “period of suspended work on the whaling book” (Parker’s words in the first volume of Herman Melville: A Biography, page 816) to make Hawthorne feel super-duper-welcome at Arrowhead, but the anticipated visit had to be postponed. In February Melville not-so-politely declined to write something for Holden’s Dollar Magazine, then owned and edited by his friends Evert and George Duyckinck. Although he would not give reasons to Evert, Melville’s view of the job as a “small thing” implies that lack of opportunity to write a magazine article was not one of them.20 Subsequently, his break from the Whale book in late April and early May gave Melville the chance to do or oversee home improvements and farm work. In May he had to plant potatoes and corn. When it rained, he wrote—splendidly, as evidenced by those incredible letters to Hawthorne in April, May, and June 1851.

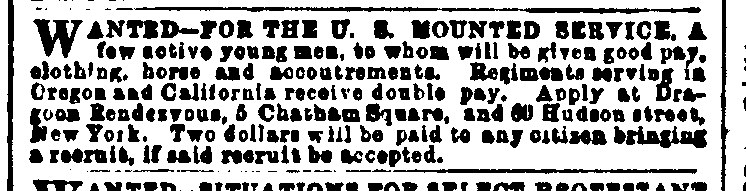

Even further back, in December 1850, the grind of daily work on “The White Whale” had not stopped Melville from plotting dozens of other writing projects. Maybe ghost-writing or ghost-editing a narrative of far western travel was one of the fifty unnamed “future works” alluded to in Melville’s Friday the 13th letter to Evert A. Duyckinck.21 Hyperbole aside, we do know that Melville by 1849 had already contemplated a rewrite of Israel Potter’s pamphlet biography.22 The timing of suspended work on Moby-Dick allows for the possibility at least of his beginning a creative rewrite of PSGC’s 1843 journal in March or April 1851 and discreetly forwarding it during the hiatus in early May. Did Melville’s “flying visit” to New York City before May 16th include a visit to the Dragoon Rendezvous, either 5 Chatham Square or 60 Hudson street? Recruits were then “WANTED—FOR THE U. S. MOUNTED SERVICE,” as advertised in the New York Herald for March 4, 1851.

Brevet Colonel C. A. May, 2nd Dragoons was the officer in charge of the Dragoon Rendezvous in New York City. And Albany, with the temporary expansion of recruiting offices in March 1851.23 Popular hero of Resaca de la Palma in the Mexican War, Charles Augustus May aka “Charley May” had served as Commandant at Carlisle Barracks, PA until replaced in 1849 by Philip St. George Cooke. As Superintendent of the New York station in 1851, B. Col. May regularly communicated with Lieut. Col. Cooke at Recruiting Headquarters, Carlisle Barracks.

Image Credit: Lieutenant Colonel C. A. May in John Frost’s Life of Major General Zachary Taylor (New York, 1847) via Northern Illinois University Digital Library.

Inspired by recent encounters with Hawthorne, in particular by their heady and hearty barn-talk that March, Melville might have found a way to get the gist of their stimulating conversations into print. Echoes of Melville’s letters in the opening installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” lead me to suspect it may be haunted by Hawthorne. At any rate, coincidence or no, the narrator of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” talks to the reader like Melville talked in letters to Hawthorne. Here’s one example from the first of Melville’s Agatha letters to Hawthorne dated August 13, 1852.24 In this example, wording and structure of the Captain’s pledge to do most of the talking for his singular reader match the “and if / why I” construction in Melville's 1852 letter to Hawthorne (emphasis mine):

“… and if you are absolutely dumb, why I will sometimes answer for you.”

“And if I thought I could do it well as you, why, I should not let you have it.”

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.84865/page/n197/mode/2up

Introducing likely topics of conversation, the Captain sounds quite like Melville when promising a good time to his invited guest:

MELVILLE

“Hark— There is some excellent Montado Sherry awaiting you & some most potent Port. We will have mulled wine with wisdom, & buttered toast with story-telling & crack jokes & bottles from morning till night.”

— Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, 29 January? 1851; emphasis mine.

CAPTAIN

“We will talk on all subjects, from the shape of a horse-shoe to that of the slipper of the last favorite—say the 'divine Fanny,’ from great battles, or Napier's splendid pictures of such, down to the obscurest point of the squad drill—from buffalo bulls to elfin sprites.” —Scenes Beyond the Western Border, June 185125

These elaborate invites are similarly themed and structured. Each presents an inventory of delightful activities in store for the recipient, each inventory being divided in three main parts. Melville’s three groupings of promised events are separated by three ampersands; the Captain’s by the word from, used thrice. The invitation in each case extends to just one person: Melville to Hawthorne, the Captain to his Imaginary Friend the reader. The plural “We” brings together speaker and singular reader as joint enjoyers of good times ahead, chiefly to be spent in stimulating conversation.

A closer verbal parallel to the opening of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” appears in another letter to Hawthorne. Writing in the middle of April 1851, Melville honored Hawthorne with a mock-formal review of his latest novel, The House of the Seven Gables (Boston, 1851). Near the end of that letter, Melville pretends to have copied the sympathetic treatment of Hawthorne’s latest book from a local journal called the Pittsfield Secret Review:

You see, I began with a little criticism extracted for your benefit from the “Pittsfield Secret Review,” and here I have landed in Africa.

—Letter to Hawthorne. 16 April? 1851; emphasis mine.

Melville’s phrase “extracted for your benefit” is echoed in the Captain’s personal address to the reader at the start of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border,” specifically in the vow “never even to transcribe for your benefit” (immediately qualified by “unless I change my mind.”) The shared three-word-phrase or “trigram” for your benefit marks something beyond a strictly verbal match. Not only the phrasing is the same, but also the referent of your, in the sense of the writer’s imagined reader: Melville’s Hawthorne, the Captain’s Imaginary Friend. Real or hypothetical, the reader in each case is supposed to be sole beneficiary. Also the same, the designated benefit—or lack thereof, as the Captain promises “never to transcribe” before hedging. In each case the thing under discussion is COPIED TEXT.

As imaginatively stipulated by each writer, the gift (bestowed or withheld) is manually copied text from a hidden or obscure source: Melville’s “secret” literary journal; the Captain’s private diary. In the April 1851 letter to Hawthorne, Melville claims to have “extracted” his admiring notice of House of the Seven Gables from a local journal devoted to secrecy, as declared in its title “Pittsfield Secret Review.” In June 1851 the Captain (oddly preoccupied, he will soon admit, with the “terrible” ordeal of “publishing a book”) initially disclaims any intention to copy or “transcribe” from his yet unpublished diary. From the first, the Captain’s desire “to talk” rather than “transcribe” is framed as “a secret.”

For Hawthorne’s “benefit” in April, Melville has “extracted” or copied a glowing commendation of House of the Seven Gables from a “Secret” source. For the friendly reader’s “benefit” in June, the Captain may or may not “transcribe” (copy) diary entries in manuscript for eventual publication. What’s the big secret? That he wants to talk and just needs a good listener.

As he goes on to confess, the Captain fears injury to his “military reputation” should “my unamended scribblings” (“scribblings unamended” in the 1857 book version) appear in print. Speaking of scribblings, Melville privately used the Captain’s plural form exactly once, with reference to his (Melville’s) own poetry in manuscript. Before sailing for San Francisco in 1860, Melville hoped his old friends the Duyckinck brothers would help his wife Elizabeth and brother Allan in their effort to oversee publication of “Poems by Herman Melville.”

“If your brother George is not better employed, I hope he will associate himself with you in looking over my scribblings.” —Letter to Evert A. Duyckinck dated May 29, 1860; emphasis mine.

Although completed in manuscript, Melville’s 1860 volume of “Poems” was rejected and never published during his lifetime, except for pieces that may have appeared in later volumes, John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) and Timoleon, Etc. (1891). Still, Melville was lucky to have kind friends he could ask for help with introducing his poetical “scribblings” to the world.

The Captain will out with his secret, providing that the reader be “honest”:

"gentle" or not,—I care not a whit,—so you are honest—

Valuing honesty more than courtesy, the Captain prefers not to flatter the addressee in conventional terms as the “gentle reader.” So much for good manners and refinement! Hawthorne, by contrast, said he always wrote for the indulgently “Kind” or “Gentle Reader,” imagined as

“that one congenial friend—more comprehensive of his purposes, more appreciative of his success, more indulgent of his shortcomings, and, in all respects, closer and kinder than a brother--that all-sympathizing critic, in short, whom an author never actually meets, but to whom he implicitly makes his appeal whenever he is conscious of having done his best.” —Author’s Preface - The Marble Faun.

Who dont want a sympathetic friend? In print, as writers, both the Captain and Hawthorne selectively and to some extent conventionally endeavor to commune with one friendly reader. In that 1856 Author’s Preface Hawthorne sounded doubtful of any audience, ruefully supposing that his long beloved “Gentle Reader” was dead and gone to “the paradise of gentle readers.” Possibly the existence and fate of Hawthorne’s “Gentle Reader” had been debated in Berkshire County, Mass. years before, in Hawthorne’s parlor or Herman Melville’s barn. Such a debate could have turned on the relative merits of honesty and courtesy. Seeking appreciation, Hawthorne wished to be indulged and humored by his special friend. In other words, Hawthorne’s Gentle Reader should be a good Liar. Contra Hawthorne, our Captain of U. S. Dragons wants a truth-teller.

More like Melville than Hawthorne, the Captain demands honesty of his ideal reader. He does not give a fig, “not a whit” for the stiff, artificial brand of kindness traditionally imputed to the “Gentle Reader.” To Hawthorne, as a kind of pre-condition for engaging in social intercourse, a matter of policy, Melville similarly elevated the virtue of honesty (along with charity = love) over pretensions of gentility:

With no son of man do I stand upon any etiquette or ceremony, except the Christian ones of charity and honesty.

Plotting to jump ship in Mardi, Melville’s fictive narrator chose Jarl, “an honest, earnest” Viking, to be his fellow-deserter. As unfolded in Chapter 3, A King for a Comrade, only Jarl will do for a kingly companion, among the whole crew of the whaleship Arcturus. (That is, before Taji takes up with congenial King Media and three other traveling companions, all talkers.) Jarl’s best features are keeping quiet (“for he was exceedingly taciturn”) and being honest; the phrase honest Jarl occurs 9 times in the first volume. Queequeg in Moby-Dick with his tomahawk-pipe, tattoos, and “purplish-yellow” complexion is similarly honored for the content of his character (despite his frightening, decidedly ungentle appearance) since “a man can be honest in any sort of skin” (Chapter 3: The Spouter Inn).

To recap, Melville’s known letters to Hawthorne and the June 1851 installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” reveal imaginative writers intensely bent on truth-telling. Truth-tellers themselves, Melville and the narrating Captain of U. S. Dragoons crave honesty in their readers, too. Both seem unconcerned with etiquette, equally ready to dispense with ceremony and drop formalities of address like “gentle reader” (youthfully used by Melville in the second of his pseudonymous 1839 "Fragments").26 Of their one ideal reader, as directly addressed in 1851, each writer demands honesty. For being honest the reader is rewarded with secret truth.

Melville's "grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne" (that godlike Hawthorne says NO! in Thunder) comes in the form of a "Secret Review." As we have seen, the Captain starts off his narrative of far-western travel and adventure with a true confession. Presented as “a secret,” this writer’s profoundest desire is for “a good listener” with whom he can talk. Almost immediately, the honest if not necessarily “gentle” or refined reader is thus enlisted as the writer’s “Imaginary Friend.” Invented conversations between wandering dragoon and his imaginary prairie friend energize all thirteen installments of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.” So regularly and compellingly that the dialogues often seem as or more important than the scenery.

All I want is a good listener.

Hawthorne was legendary for listening and may well be the G. O. A. T. Melville obviously knew how blessed he was in having him nearby. Hard to find such a one in the real world, as hinted in Moby-Dick:

Seldom have I known any profound being that had anything to say to this world, unless forced to stammer out something by way of getting a living. Oh! happy that the world is such an excellent listener! — Chapter 85: The Fountain

Translate: the Whale does well to be voiceless since nobody listens anyway. The world we know is often not such a great LISTENER, but it's wonderful to discover, behind the irony and sarcasm, that Melville's narrator identifies with hard-pressed speakers looking to find one. In essence, Ishmael's exclamation rephrases Melville’s point to Hawthorne about the general reception of truth-tellers. The Truth Is Out There, but the working writer who proclaims it will “go to the Soup Societies” or worse, "die in the gutter."27 Back then, getting paid in the real world and England could require deletion of matter deemed too unorthodox, prurient, or otherwise offensive to the "tender consciences of the public."28 Confessedly damned by dollars, Melville needed cash but still felt impelled to tell the truth in his writing. It’s the same conflict of aims and agendas you find in the best Hallmark movies, except for the ending. In Melville’s well-known take on the business of writing, the conflict of practical vs. aesthetic urges resulted in the sad outcome that (as he famously put it to Hawthorne) “all my books are botches.”

In a mean old world, the only thing less marketable than TRUTH is POETRY. Far more anxiously and cautiously than Ishmael, another of Melville’s writer-narrators worried about reaching a sympathetic reader of verse in the posthumously published sketch “House of the Tragic Poet.”

“You see, good reader, I am making a confidant of you, and that too in matters that another tyro-editor more discreet would very likely keep to himself, seeking to pass himself off as a veteran. But I desire to make a friend of you, and without frankness how accomplish it?”29

Melville’s sketch was meant to introduce the mixed collection of verse and prose titled Parthenope in manuscript and 21st century print editions.30 Here represented as a fledgling editor, Melville's narrator tries to confide in and “make a friend” of the “good reader.” To make a friend now requires honesty on the narrator's part. No frankness, no friend. In being frank, Melville’s would-be editor exposes something of his own poetical soul. As fugitive poetry lover and promoter if not fugitive poet, this “tyro” editor’s main object is to introduce somebody’s verse—whose is hard to say. Authorship questions aside, Melville’s novice poetry editor aims to gain something like what Melville had briefly in Berkshire, and what the Captain of U. S. Dragoons self-consciously refashioned by making the honest reader his Imaginary Friend.

Melville’s novice editor in “House of the Tragic Poet” is looking for a friendly reader of two ambitious and highly imaginative poems, namely At the Hostelry and An Afternoon in Naples in the Time of Bomba. Besides having to be honest, the reader sought by the narrator of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” must likewise be someone capable of appreciating poetry along with the romance of western scenery and action. The exclusive call for one “friendly” person who can bring “a poetic mood” to the experience of reading or listening is a later development in the series, first communicated openly in the July 1852 installment. Wondering whom to address, the narrator finally appeals to a redefined target audience of one poetry aficionado. Regarded by somebody as exceptionally meaningful, this passage was copied and transported without explanation to the front of the book version, as a kind of epigraph:

“I ADDRESS not, then, the shallow or hurried worldling; but the friendly one, who, in the calm intervals from worldly cares, grants me the aid of a quiet and thoughtful, and, if it may be, a poetic mood."31

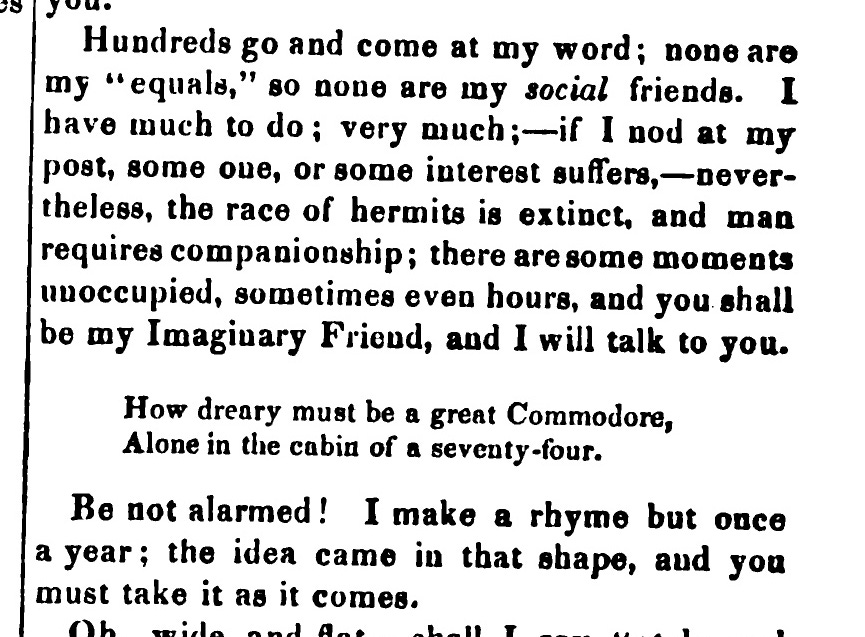

In light of the “poetic mood” begged of the ideal reader in the later installment and epigraph, it is worth noting how early the turn to poetry begins in “Scenes Beyond the Western Border.” With the first installment barely underway in June 1851, the Captain starts talking to his newly recruited Imaginary Friend, and the first thing out of his mouth is a rhymed couplet.

Hundreds go and come at my word; none are my "equals," so none are my social friends. I have much to do; very much;—if I nod at my post, some one, or some interest suffers,—nevertheless, the race of hermits is extinct, and man requires companionship; there are some moments unoccupied, sometimes even hours, and you shall be my Imaginary Friend, and I will talk to you.

How dreary must be a great Commodore,

Alone in the cabin of a seventy-four.

Hard to say which is more unexpected, the burst into verse or the nautical imagery. Both form and content seem a little out of place on “The Prairie.” Yet here we are, nevertheless, sympathizing with the lonesome plight of a high Commodore at sea when physically isolated from others by the tyranny of custom, deprived of good fellowship by reason of his exalted rank.

Be not alarmed! I make a rhyme but once a year; the idea came in that shape, and you must take it as it comes.

“Keep cool” feels like good advice at this juncture. I was about to say the Captain’s “rhyme” sounded like an outtake from White-Jacket Chapter 6. Better to relax as instructed. That snatch of nautical verse was just a fluke, “and you must take it….” Wait, what? I was also going to observe yet again, by way of a closing summary, how the narrator’s language in the first installment of “Scenes Beyond the Western Border” echoes Melville when addressing Hawthorne. Examples cited herein are similar promises to do the talking; invites with tripartite agendas that begin “We will have” (Melville) and “We will talk (Captain); the phrasing “and if / why I” as used in Melville's first “Agatha” letter to Hawthorne; and the copying of text “for your benefit,” framed as a “secret.”

That makes four specific instances and here’s a fifth in “and you must take it,” Melville’s words the year before in Hawthorne and His Mosses. Although Melville there was not exactly writing to Hawthorne, the shared sequence of five consecutive words occurs in his pseudonymous review-essay all about Hawthorne. Half a fifth, at least. Either way it’s a lot of talk already for a chronicle of military life on the road to Santa Fe. With too much of Melville on Hawthorne, seemingly, even for a Romance.

Complicating the publication history of Scenes and Adventures are the interpolated "Indian romances" of Mah-za-pa-mee and Sha-wah-now in the July 1842 Southern Literary Messenger, both of which had previously appeared over the signature of "P.S.G.C." in the Military and Naval Magazine of the United States; Mah-za-pa-mee in August 1835; Sha-wah-now as A Tale of the Rocky Mountains in September 1835. Both Indian tales as well as the story of Hugh Glass (a clever rewrite of the widely circulated account of The Missouri Trapper by James Hall) had already seen print in late 1830 and early 1831, as newspaper sketches published in the St. Louis Beacon over the signature of "Borderer." Some Incidents in the Life of HUGH GLASS, a Hunter of the Missouri River originally appeared in the St. Louis Beacon on December 2 and December 9, 1830. “A Tale of the Rocky Mountains” (Sha-wah-now), also signed “Borderer,” premiered in the St. Louis Beacon for January 13, 1831. “Mah-za-pa-mee” first appeared in St Louis Beacon on February 17, 1831; reprinted therefrom in the July 1831 issue of the Illinois Monthly Magazine.

While stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Philip St. George Cooke wrote his Baltimore cousin John Pendleton Kennedy on March 14, 1855 to get Kennedy’s “advice or assistance” with Cooke’s project “to have a modest volume published, to be called, “Fragments of a Military Life.” By then the proposed volume had already been rejected by the Harpers, Putnam, and Appletons. To Kennedy, Cooke described the book as a collection “consisting of certain S. Lit. Messenger articles,” specifying that “there were two series, in ‘42 & ‘51-’52” which he has improved through revision: “At my leisure I have added to, polished, & corrected them.” Letter to John Pendleton Kennedy dated March 14, 1855; accessible on microfilm in The John Pendleton Kennedy papers. https://www.archives.gov/nhprc/projects/catalog/john-pendleton-kennedy

On the history and literary uses of the Fragment form in the United States, including a treatment of Melville’s 1839 “Fragments from a Writing Desk,” see Daniel Diez Couch, American Fragments: The Political Aesthetic of Unfinished Forms in the Early Republic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022). https://books.google.com/books?id=Y0pTEAAAQBAJ&pg

Strangely absent, the story of Cooke’s role in the Stephen Watts Kearny expedition, told decades later in The Conquest of New Mexico and California in 1846-1848 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1878).

Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, Sailor Talk: Labor, Utterance, and Meaning in the Works of Melville, Conrad, and London (Liverpool University Press, 2021) page 177. https://books.google.com/books?id=pm9vEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA177&lpg#v=onepage&q&f=false

Herman Melville, here quoted from his manuscript notes in Chase’s Narrative (New York: W. B. Gilley, 1821) now at Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge Mass. Persistent Link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:2641693?n=21

Francis Otto Matthiessen, American Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 1941) page 383.

https://books.google.com/books?id=dGPmCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA383&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Philip St. George Cooke, Letter to John Esten Cooke dated May 15, 1851; now in the John Esten Cooke Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. https://archives.lib.duke.edu/catalog/cookejohn

That’s according to Theodore F. Wolfe in Literary Shrines: The Haunts of Some Famous American Authors (Philadelphia, 1895) page 191. Wolfe heard all about it in a personal interview with Melville:

This visit—certainly unique in the life of the shy Hawthorne—was the topic when, not so long agone, we last looked upon the living face of Melville in his city home. March weather prevented walks abroad, so the pair spent most of the week in smoking and talking metaphysics in the barn, —Hawthorne usually lounging upon a carpenter's bench. When he was leaving, he jocosely declared he would write a report of their psychological discussions for publication in a volume to be called “A Week on a Work-Bench in a Barn,” the title being a travesty upon that of Thoreau's then recent book, “A Week on Concord River,” etc.

https://books.google.com/books?id=Oo5DAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA191&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Melville called their philosophical talk “ontological heroics” in his letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne dated June 29, 1851; transcribed by Julian Hawthorne in Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife (Boston, 1884) pages 398-400. https://books.google.com/books?id=FFHwgQN-aEQC&pg=PA400&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Letters to Hawthorne cited herein also may be found in the 1993 Northwestern-Newberry Edition of Melville’s Correspondence, edited by Lynn Horth. https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810109957/correspondence/

Quoted here from Twenty Days with Julian and Little Bunny: A Diary (New York, 1904) page 26.

https://archive.org/details/twentydayswithju00hawt/page/26/mode/2up

Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, letter of May 7, 1851 to her sister Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. Here quoted from Melville in His Own Time, ed. Steven Olsen-Smith (University of Iowa Press, 2015) page 76. https://books.google.com/books?id=b1TpCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA76&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Also quoted and discussed in the chapter by Wyn Kelley on “Melville’s Flummery” in the Edinburgh Companion to Nineteenth Century American Letters and Letter-Writing, ed. Celeste-Marie Bernier, Judie Newman, and Matthew Pethers (Edinburgh University Press, 2016) page 568. https://books.google.com/books?id=B3AxEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA568&dq#v=onepage&q&f=falsevi

Emphasis mine. Formerly and tentatively dated 1 June? 1851 in Melville scholarship, this delicious, endlessly quoted letter to Hawthorne is assigned to early May 1851 by Hershel Parker in the first volume of Herman Melville: A Biography, 1819-1851 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) page 841.

https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/17041/herman-melville

“Like many silent men he was a good listener” in the words of George Edward Woodberry, Nathaniel Hawthorne/Chapter 7.

Leon Howard, Herman Melville: A Biography (University of California Press, 1951) page 160. Emphasis mine.

https://books.google.com/books?id=zih9EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA160&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

“So Herman has another book ready has he?” Letter to Augusta Melville from Mary Blatchford on April 22, 1851; held by the New York Public Library, Gansevoort-Lansing collection. Mary Blatchford’s letter to Augusta is quoted in Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography, Volume 1 1819-1851 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) page 837. https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/17041/herman-melville

As related by Hershel Parker in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 1 on page 837, when “Herman dismissed her as his copyist, late in April,” Augusta “made her escape to the Manor House, thinking the manuscript was about ready to go to press.”

Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 1, pages 839-842. Fire on January 23, 1852 destroyed everything Craighead had in his third-floor rooms at 112 and 114 Fulton Street. As reported in the New York Times on January 24, 1852 Craighead lost equipment worth $25,000 but quickly “made arrangements to continue his business, having hired rooms and procured type and presses.”

Augusta’s letter to Allan Melville on May 16, 1851 is quoted by Parker in Herman Melville: A Biography Volume 1, page 840. https://books.google.com/books?id=OrTOQR4QyKIC&pg=PA840&lpg#v=onepage&q&f=false

Letter to Evert A. Duyckinck, February 12, 1851. The Letters of Herman Melville, edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman (Yale University Press, 1960) page 120. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.8l4865/page/n159/mode/2up

Letter to Evert A. Duyckinck, December 13, 1851. Transcribed in the 1993 Northwestern-Newberry Edition of Melville’s Correspondence, edited by Lynn Horth, page 174. Image via NYPL Digital Collections.

In London Melville bought an old map as future source material, “in case I serve up the Revolutionary narrative of the beggar” Israel Potter. See the 1989 Northwestern-Newberry Edition of Herman Melville’s Journals, edited by Howard C. Horsford with Lynn Horth, page 43 with commentary in the Editorial Appendix, page 172. https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810108233/journals/

On March 15, 1851, Philip St. George Cooke wrote from the Recruiting Service “H. Q.” at Carlisle Barracks to request “that one hundred dollars recruiting funds may be sent to B. Col. C. A. May 2 Drag. at Albany N. Y. with a set of recruiting blanks,” enclosing “two requisitions for clothing & arms for that new rendezvous.” National Archives, Letters Received by the Adjutant General, 1822-1860, C106 via fold3 https://www.fold3.com/image/293715086.

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, 13 August 1852. Manuscript images are accessible via Harvard. MS Am 188 (173). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.p. 6

Persistent Link: https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:1171481?n=6

Ballet superstar Fanny Elssler (1810-1884) of Austria is the “divine Fanny” referenced here. Her famous slipper keeps company with that of Cinderella in Hawthorne’s short story A Virtuoso’s Collection: "Fanny Elssler's shoe, which bore testimony to the muscular character of her illustrious foot."

Melville’s narrator directly addresses the “gentle reader” in “Fragments from a Writing Desk No. 2” by L. A. V., first published in the Democratic Press, and Lansingburgh Advertiser on May 18, 1839. Included in the 1987 Northwestern-Newberry Edition The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860, edited by G. Thomas Tanselle, Harrison Hayford and Hershel Parker, pages 197-204 at 200. https://books.google.com/books?id=WdSJKd3weBcC&pg=PA200&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Melville’s words after rejection of The Two Temples by Putnam’s magazine. Letter to George P. Putnam dated May 16, 1854. https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/herman-melville-collection-william-s-reese/rejection-two-temples-refusing-be-photographed-637/158135

“House of the Tragic Poet” in Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings, edited by G. Thomas Tanselle, Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, Robert Sandberg and Alma MacDougall Reising (Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 2017) page 142. https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810111141/billy-budd-sailor-and-other-uncompleted-writings/

In Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings, pages 139-202 with “Supplementary” prose sketches at 203-224. Parthenope including the longer poems “At the Hostelry” and “An Afternoon in Naples in the Time of Bomba” also appears with “Posthumous & Uncollected” works in Herman Melville: Complete Poems, edited by Hershel Parker (Library of America, 2019) on pages 789-859. There, “House of the Tragic Poet” may be found on pages 795-800.

Scenes and Adventures in the Army, epigraph taken from the July 1852 installment of Scenes Beyond the Western Border in the Southern Literary Messenger, page 413.

https://books.google.com/books?id=HVMFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA413&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false