Saint Elizabeth's miracle of roses in Melville's "Rosary Beads"

I. Take the best right now.

Without Price is the second of three short, devotionally oriented stanzas, numbered and strung into poetic Rosary Beads in Herman Melville’s uncompleted collection of manuscript poetry and prose, Weeds and Wildings.1 As editorially numbered in the Northwestern-Newberry Edition, the first bead-stanza (The Accepted Time) proclaims with the ardor and urgency of a carpe diem love poet that now is the time to “Adore the roses.” How? As beautiful flowers, literally, or lovers, figuratively? Emblems of Art, or mystical religious symbols? Hard to tell. Endless signifying is the glory of Melville’s poetic rosary, more amenable to meditation and prayer and veneration of Linda Ronstadt than ultimate resolution.

The next bead riddles on roses that cannot be bought or grown at home in your garden:

Without Price

Have the Roses. Needs no pelf

The blooms to buy,

Nor any rose-bed to thyself

Thy skill to try:

But live up to the Rose's light,

Thy meat shall turn to roses red,

Thy bread to roses white.

They’re more than organic, evidently, yet not for sale at any farmer’s market. Without Price in the heading really means Free, like the spiritual food offered “without price” or “without cost” in the first verse of Isaiah chapter 55. In Christian Bible exegesis the phrase in Isaiah has been understood to figure Jesus as the “bread of life” and “living water,” with particular reference to chapters 6 and 7 in the Gospel of John.2

Whatever else they might be or metaphorically mean, roses—Roses—such as these are unobtainable by natural methods of horticulture. You only get them by living right, “up to the Rose’s light.” This pre-condition of saintly conduct seems personified in Saint Clare of Assisi. Fittingly and maybe not coincidentally, since Melville made “Sister St. Clare” the star of “A charm in Life,” the cancelled manuscript poem in Weeds and Wildings that originally formed the first of “Four Beads from a Rosary.”3 As very recently and reasonably proposed by Christina Choon Ling Lee

The stanza’s focus on St. Clare suggests that the remediating work of “Rosary Beads,” is to learn how to become more virtuous by living a life of humble devotion.”4

Do right, with the Holy Ghost your guide, and your everyday groceries will be magically transmuted: “Thy meat shall turn to roses red, / Thy bread to roses white.”

In print, commentators on Without Price often connect the transformation of meat and bread into roses with Holy Communion, the Christian sacrament of the Eucharist. In a pioneering 1966 essay, Richard Bridgman saw “a curious pagan version of the Eucharist” in the closing miracle.5 In the early 1970’s William H. Shurr discerned a “sacramental transformation” in the change of red and white roses to meat and bread, potentially carrying “a profound theological meaning if the ‘Rose’ is Christ.”6 Degreed in theology as well as literature, Shurr made sure to generalize the perceived effect of Melville’s language and imagery as “sacramental.” John Bryant, wrestling with changes in the order of Melville’s rose poems along with the merit and meaning of individual pieces, found a promise of transfiguration and wisely left it at that:

“Have the Roses” (live up to their light and you will be transfigured). 7

In the 21st century critics like William B. Dillingham have been more willing to name the Church doctrine supposedly evoked:

In “Rosary Beads,” Melville’s most direct treatment of his rose religion, the marvelous power of the rose (and by implication, of the imagination) is described in terms suggestive of Transubstantiation.8

In similar terms, with similar confidence, Robert Milder makes it Transubstantiation, artfully secularized:

“In the second stanza of “Rosary Beads” the language of Christian miracle (transubstantiation) is applied to the metamorphosis of sense experience into a continuing secular miracle of Paterian intsensity.”9

Milder and Dillingham readily specify the Eucharist miracle of bread and wine becoming the body and blood of Jesus during Holy Mass, without Shurr’s qualifying “if.” Bryant, thankfully, did not bother with trying to separate out religious, aesthetic, and sexual codes in Melville’s rose-poems, but conjoined them in pursuing Melville’s theme or motif of transfiguration in “As They Fell.”

A little weirdly, critics who identify Transubstantiation as Melville’s allusive point of reference in Without Price typically take the roses there for a “secular miracle,” independent of religious faith. Certain that faith and art “are quite different things,” Milder regards the obvious religious elements in Rosary Beads as trappings, costumery borrowed from Catholicism “to deck the secular hedonism” manifested in the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.10 The most thrilling “metamorphosis” Milder can imagine is the turning of our Lord and Savior into Walter Pater—a very smart art critic. A skeptic might wonder how your average miracle can truly be a miracle without any spiritual basis or relevance. Be assured, however, secular miracles do happen in real life. Here in America, real secular miracles mostly occur in swing states during the wee small hours of the morning after a presidential election, usually around 3 a.m.

But let that go. We’re talking about one of Melville’s rose poems in “As They Fell” (a subset of Weeds and Wildings Chiefly, subtitled with A Rose or Two). As suggested above, the Bible-based title Without Price already implicates Christ by way of traditional Christian exegesis. Mindful of eucharistic language and symbolism in the Gospel of John and other New Testament texts, any knowledgeable and sympathetic reader (however devout) might well be inclined to associate the free offering of food and drink in Isaiah 55:1 with Christ and Communion. Something is missing, however, the absence of which makes a difference.

II. Tell it like it is.

The previous stanza The Accepted Time took rose-worship to church in metaphors of a service fully equipped with priests and censers. Meaningful celebration of the Eucharist in the next would require some kind of sacramental wine. Without it, The Lord’s Supper is off the table. No wine or grape juice means no possibility of Holy Communion. Fact check: there is no wine in Without Price or anywhere in Rosary Beads. Deal-breaker, right? Not necessarily. You have to allow for the ingenuity of Mormons and English professors. Bridgman constructed a dubious pagan Eucharist to account for Melville’s wineless lines. Brian Yothers concedes the looseness of Melville’s alleged allusion to transubstantiation but keeps it anyway—as a relique of critical orthodoxy, perhaps:

Here we see the roses as a kind of gratuitous gift of beauty. The idea of meat and bread changing to roses plays loosely off the change of bread to the body of Christ in transubstantiation in the same way that the poem as a whole plays off of the relationship between the metaphorical flowers of the rosary and literal roses.11

As hinted already, however, the gift of roses is not entirely “gratuitous.” Although free, without monetary cost, the roses come only after fulfillment of the requirement to “live up to” something, by right conduct. In “charm in Life” the lilies and roses preferred by Sister St. Clare embody “Christ’s sweetness and light.” Living up to that light triggers the gift of roses without price. Astonishing in red and white, these supernaturally generated miracle-roses are, paradoxically, the realest in Rosary Beads.

I mean, red roses and white roses are differentiated by color with surprising clarity for a free-floating allusion to the Eucharist.

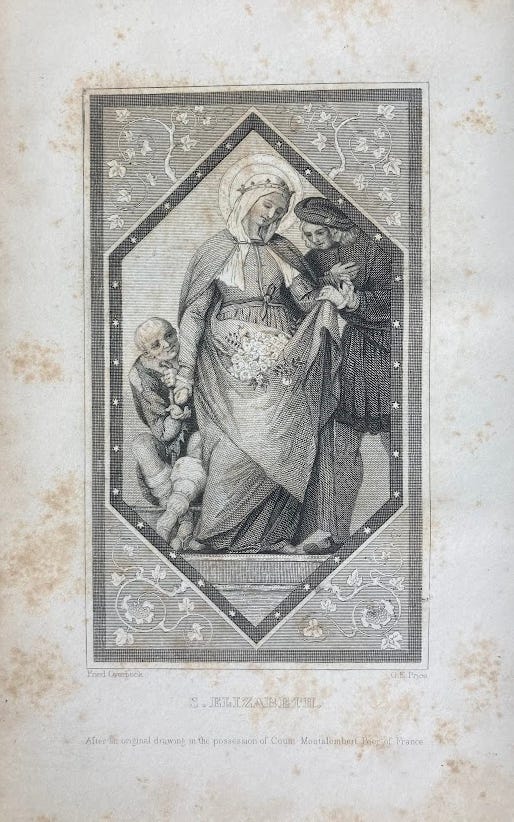

More directly and precisely, Melville’s image of red and white roses that used to be meat and bread alludes to a delightful highlight in the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary, the miracle of the roses. The story is well told in a book we know Melville owned and commended to family members, The Life of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary:

Elizabeth loved to carry secretly to the poor, not alone money, but provisions and other matters which she destined for them. She went thus laden, by the winding and rugged paths that led from the castle to the city, and to the cabins of the neighbouring valleys.

One day, when accompanied by one of her favourite maidens, as she descended by a rude little path—(still pointed out) —and carried under her mantle bread, meat, eggs, and other food to distribute to the poor, she suddenly encountered her husband, who was returning from hunting. Astonished to see her thus toiling on under the weight of her burthen, he said to her, “Let us see what you carry”—and at the same time drew open the mantle which she held closely clasped to her bosom ; but beneath it were only red and white roses, the most beautiful he had ever seen and this astonished him, as it was no longer the season of flowers. Seeing that Elizabeth was troubled, he sought to console her by his caresses, but he ceased suddenly, on seeing over her head a luminous appearance in the form of a crucifix. He then desired her to continue her route without being disturbed by him, and he returned to Wartburg, meditating with recollection on what God did for her, and carrying with him one of those wonderful roses, which he preserved all his life. At the spot where this meeting took place, he erected a pillar, surmounted by a cross, to consecrate for ever the remembrance of that which he had seen hovering over the head of his wife.12

In humbly ministering to the poor Elizabeth did all the moralizing speaker asks in the second (or third, reviving A Charm in Life) segment of Rosary Beads. Through her generous and exemplary foodservice this princess did “live up to the Rose’s light” and duly received the promised blessing of red and white roses, unnaturally beautiful and magically transmuted from ordinary meat and bread. Faithfully narrated by Montalembert, the story of Elizabeth’s miracle roses is the poet’s unnamed exemplum in Without Price.

Elizabeth’s recorded experience of the miracle of roses is one of the fabulous “legends of the Old Faith” that Melville commended to his brother-in-law John Hoadley in 1877, not long after the publication of Clarel.

“These legends of the Old Faith are really wonderful both from their multiplicity and their poetry. They far surpass the stories in the Greek mythologies. Don’t you think so? See, for example, the Life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary.”13

Melville had already given his copy of Montalembert’s Life of Saint Elizabeth to his cousin Kate, calling it "that book of the sainted queen." 14 And already mined it extensively when composing Clarel. Kevin J. Hayes has cited one possible debt in Clarel Part 1 Canto 14, for a tradition about the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.15 Although uncredited in Clarel, Montalembert is definitely Melville's main authority for the ritual separation and care of lepers during the Middle Ages described in "Huts," Part 1 Canto 25. Melville paraphrases Montalembert again in “Of Rome,” Part 2 Canto 26 when depicting Derwent's uncharacteristic partiality for "sweet” Catholic legends; and Derwent's belief in the appeal of saints' lives to future bards, done with plundering Greek myths, as a “second mine” of poetry.16

Montalembert's enthusiasm for the 13th century as a vanished age of "artless simplicity" and piety also informs the "impetuous" neo-medievalism of Ungar in Part 4 of Clarel, displayed for example in praise of Saint Louis IX and the grandeur of cathedral architecture (Canto 10 A Monument); and the later, gloomier rant on the modern sway of atheism and popular science in Canto 21, “Ungar and Rolfe."17

Elsewhere in Weeds and Wildings, overt references in prose to St. Elizabeth’s miracle of the roses appear at the end of two superseded dedications or toasts to an unnamed female “friend” of the unnamed speaker. Both manuscript versions close with a gift of imaginary roses, floridly presented:

“the after-roses of Paestum…and in the Hesperides to come, the eternal ones of her who wears both the crown and the garland—St. Elizabeth of Hungary.”

“roses without thorns, eternal ones, the roses of Elizabeth of Hungary.” 18

Christina Lee has helpfully linked Melville's prose invocations of Saint Elizabeth to the miracle of roses passage from Montalembert’s hagiography.19 Accessible online, Lee's 2021 dissertation sparkles with mentions of Saint Elizabeth—none of which connects her with Rosary Beads. When explicating Without Price, Lee considers the transformation of meat and bread into roses chiefly in relation to the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross, as foreshadowed and symbolized in the Last Supper.

Most intriguing to me is Lee’s suggestion that Melville’s poetic “Rosary Beads” may correspond even faintly to Catholic Mysteries of the Rosary. As the second “bead,” Without Price seems well matched to the Light Mysteries of the Rosary which culminate with the Institution of the Eucharist. As Lee points out, however, the whole group of Luminous Mysteries was first introduced in 2002 by Pope John Paul II. In Melville’s day the Holy Rosary still had three sets of mysteries: 1) the five joyful mysteries; 2) the five sorrowful mysteries; and 3) the five glorious mysteries. While closely concerned with the crucifixion of Jesus, the Five Sorrowful Mysteries do not specifically feature the Last Supper, as Lee also recognizes.

III. Going down slow

Hypothetical correspondences with the Catholic Rosarium start breaking down in Grain by Grain, the third of Melville’s rosary-bead stanzas, or get stuck in the Sorrowful Mysteries. Same goes for tempting ties with Julia Roberts and her character’s tripartite life in Eat, Pray, Love. As arranged in Rosary Beads the sequence is Love, Pray, HODL. Grain by Grain leaves us with rose-garden under siege by relentlessly "creeping" desert sands:

Grain by grain the desert drifts

Against the Garden-Land;

Hedge well thy Roses, heed the stealth

Of ever-creeping Sand.

Here and elsewhere, acknowledgments of human mortality, however poetically expressed, do not make Melville the author of Death or its partisan. Obviously Herman Melville did not invent Time, Death, or the cycle of Seasons. Academic commentators for some reason like to pretend he did. And get happy about it, as when Elizabeth Renker climaxes the last chapter of Realist Poetics in American Culture with her claim that Melville’s poem Rosary Beads

“ends with a realist obliteration of this idealist garden.”20

Although plainly threatened and in the long run inevitable, maybe, obliteration by “ever-creeping Sand” is not yet achieved in this the third stanza of Rosary Beads. Else why trouble at all with hedging and heeding? Melville’s advice then, or that of his priestly speaker, is for the living. Then, too, Garden and Desert are both metaphors and therefore open to multilayered interpretation. As ever, depending on quality of evidence and arguments, some interpretations will seem more reasonable and persuasive than others. In print, Renker has prudently modified her earlier treatment of Rosary Beads, in part by shifting to a direct quote from the first stanza.21 Unfortunately, as now given in Realist Poetics on page 136, the first line reads “Adore the Roses not delay.” Renker’s not is a typo for Melville’s word nor. On the bright side, in the clown-world of Academia the poet’s words never matter as much as the critic’s.

More importantly, Reader, whose side are you on? Garden or Desert?

The garden and starkness of contrast in Grain by Grain recall Ishmael’s “insular Tahiti” of the soul, surrounded by an ocean of psychic terrors in the Brit chapter of Moby-Dick (1851). Another parallel in Melville’s writings, cited by Bridgman in the mid-1960’s, occurs in Pierre; Or, The Ambiguities (1852):

… Memnon's sculptured woes did once melodiously resound; now all is mute. Fit emblem that of old, poetry was a consecration and an obsequy to all hapless modes of human life; but in a bantering, barren, and prosaic, heartless age, Aurora's music-moan is lost among our drifting sands, which whelm alike the monument and the dirge. [emphasis mine]

A versified rendition of this existential dilemma may be found in The Enthusiast, a poem from Timoleon, Etc. There Melville’s aging speaker faces down the same desert with for him rhetorical questions like this:

Shall Time with creeping influence cold

Unnerve and cow?

No, but fighting back means you have to hedge and heed like a Crusader, say Joe Sample. Melville’s conceit here of Time as creeping seems echoed in the “ever-creeping Sand” imaged in the last stanza of Rosary Beads. If the Desert be Death, metaphorically speaking, then Sand would be Time, “ever-creeping.” Time flies, too, like hurricanes and pouring rain Gregg Allman said in the first song on Eat a Peach. But in Rosary Beads it creeps “Grain by grain,” like the sand of an hour-glass. In prose, Melville’s sketch of Hunilla on Norfolk Island in The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles features a similar conjunction of images and figures—Time, Death, Sand, and Hour-Glass—together with humble but nonetheless potent symbols of faith in the slanted, weather-worn Cross of sticks on Felipe’s grave and his widow’s crucifix, worn down through grief:

The mound rose in the middle; a bare heap of finest sand, like that unverdured heap found at the bottom of an hour-glass run out. At its head stood the cross of withered sticks; the dry, peeled bark still fraying from it; its transverse limb tied up with rope, and forlornly adroop in the silent air.

Hunilla was partly prostrate upon the grave; her dark head bowed, and lost in her long, loosened Indian hair; her hands extended to the cross-foot, with a little brass crucifix clasped between; a crucifix worn featureless, like an ancient graven knocker long plied in vain.22

A sad scene, full of pathos, with no rose-garden in sight. Sentimentally and in places theatrically presented by Melville’s sailor-narrator (also a tortoise-hunter, like Hunilla) yet even bleaker than the “realist” Desert Renker sees in Grain by Grain. Good news, however, for Melville devotees: you can stop looking for Isle of the Cross! Truth be told, Basem L. Ra’ad found it now more than thirty years ago.23 Brothers and Sisters, it lies in the Enchanted Isles or nowhere.

Elizabeth Renker tries and retries to clinch her case for Melville’s brand of “realist poetics” with select quotations from the first and third stanzas of Rosary Beads. Unaccountably skipped every time: the middle one which promises a faith-based miracle of roses, famously illustrated in the life story of Elizabeth of Hungary.

There’s one rose left. Still free, but to see it you have to go to Harvard. More specifically, you need to look in the Herman Melville papers at Houghton Library, Harvard University. Rosary Beads, as ordered in the Northwestern-Newberry Edition, falls between Rose Window and The Devotion of the Flowers to their Lady. However, in the order of digital images presented online by Harvard Library, the superseded dedication written on the verso of “The Avatar” immediately precedes the leaf containing the two stanzas of “Rosary Beads” titled The Accepted Time and Without Price. 24

Persistent Link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=18

Aladdin’s palace, a certain sinner was emboldened to uplift an honest prayer for a certain kindly heretic, invoking for her roses without thorns, eternal ones, the roses of Elizabeth of Hungary.

Viewed thus, Melville’s handwritten prose invocation of Elizabeth of Hungary makes a graphic and graciously worded preface to the poem that begins on the next manuscript page.

Persistent Link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=19

Visually and thematically, the X-ed “prayer” of “a certain sinner” for a lovable “heretic” points up the focus on prayer in the title of Rosary Beads, as well as Melville’s allusion to Saint Elizabeth and her miracle of roses in the second stanza.

Or third of “Four Beads from a Rosary,” restoring an earlier manuscript title and counting the cancelled manuscript poem “A charm in Life.” Pruned to three segments and editorially re-numbered, Melville’s poem Rosary Beads appears in Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings, edited by G. Thomas Tanselle, Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, Robert Sandberg and Alma MacDougall Reising (Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 2017) on page 123; with relevant textual notes in the Editorial Appendix on pages 561 and 618-19. Text of the cancelled “charm in Life” is given on page 618.

The physical manuscript of Weeds and Wildings is held in the Melville collection at Houghton Library, Harvard University. Excellent images of manuscript pages with Rosary Beads and the rest of Weeds and Wildings (including numerous other rose poems) are accessible via Harvard Library. Full cite below with link to image of Without Price:

Persistent Link https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=19

Description Melville, Herman, 1819-1891. Unpublished poems : autograph manuscript, undated. Herman Melville papers, 1761-1964. MS Am 188 (369.1). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.Folder 1. Weeds and wildings: As they Fell.

Page sheet 10 (seq. 19)

Repository Houghton Library

Institution Harvard University

Accessed 25 August 2022

See for example Richard Bauckham, “Sacraments and the Gospel of John” in The Oxford Handbook of Sacramental Theology, edited by Hans Boersma and Matthew Levering (Oxford University Press, 2015) pages 127-8.

https://books.google.com/books?id=F2vLCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT128&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Transcribed below from the digital image of the manuscript page as presented on the Harvard Library website, https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=6.

Beads from a Rosary

I.

A charm in Life

A charm in life

And safe-conducts in death,

Says Sister St. Clare,

Are the Lilies and Roses White.

Come away from the Tulips

Poor flaunters that flare

These Lilies and Roses attain,

For theirs are Christ’s sweetness and light.

Christina Choon Ling Lee, Therapoetics In Late Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Doctoral Dissertation (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2021) page 122.

https://doi.org/10.17615/1e6v-0q98

Richard Bridgman, “Melville’s Roses.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 8, no. 2 (1966) pages 235–244 at 241 http://www.jstor.org/stable/40753898.

William H. Shurr, The Mystery of Iniquity: Melville as Poet, 1857–1891 (The University Press of Kentucky, 1972) page 272. Emphasis mine.

John Bryant, “Melville's Rose Poems: As They Fell,” Arizona Quarterly 52.4 (Winter 1996) pages 49-84 at page 73.

William B. Dillingham, Melville and His Circle: The Last Years (University of Georgia Press, 2008) page 160.

Robert Milder, Exiled Royalties: Melville and the Life We Imagine (Oxford University Press, 2006) page 234.

Milder, Exiled Royalties, page 233.

Brian Yothers, Sacred Uncertainty: Religious Difference and the Shape of Melville’s Career (Northwestern University Press, 2015) page 202.

Charles Forbes René de Tryon, Comte de Montalembert, The Life of Saint Elizabeth, of Hungary, Duchess of Thuringia (New York: D. and J. Sadlier & Co., 1884) page 155. Emphasis mine. Melville owned and marked the 1870 edition, Sealts Number 368 in the online Catalog at http://melvillesmarginalia.org/.

The National Library of Israel has the 1879 printing of the Sadlier edition, bound with The Life and Times of St. Bernard by Marie-Théodor Ratisbonne; the digitized volume is accessible via Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=zRcKTf-_xuIC&printsec=frontcover&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Letter to John C. Hoadley" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/36b51740-48f7-0137-36b1-19cceb3b2b49

Letter to Catherine Gansevoort Lansing dated October 8, 1875; tipped in at the rear pastedown of the volume now held by New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, Gansevoort-Lansing Box 335. This 1875 letter to Kate and the 1877 letter to Hoadley cited above are both transcribed in The Letters of Herman Melville, edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman (Yale University Press, 1960) on pages 244 and 256-260.

Kevin J. Hayes, Melville’s Folk Roots (Kent State University Press, 1999) page 99.

In Clarel Part 4 Canto 10, Ungar praises great medieval cathedrals as "grand minsters" that

Do intimate, if not declare

A magnanimity which our time

Would envy, were it great enough

To comprehend.

In his effusive introduction to The Life of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Montalembert similarly extols "those gigantic cathedrals, which appear as though they would bear to heaven, on the summit of their spires, the universal homage of the love and the victorious faith of Christians.” Yet unfinished Cologne, still "suspended in its glory," nonetheless offers "a challenge to modern impotence." Montalembert lists York Minster (impressive to Ungar for "majesty of mien") with other examples of majestic Christian architecture as "colossal works undertaken and accomplished by one single city or chapter, whilst the most powerful kingdoms of our time would be unable, with all their fiscality, to achieve even one such glorious and consoling victory of humanity and faith over incredulous pride" (pages 63-65).

Montalembert twins “simplicity and faith” as essential and characteristic values in the Middle Ages:

"… the two principles which were so wonderfully united in Elizabeth and her age—simplicity and faith. Now, as every one knows and says, they have disappeared from the mass of society; the former, especially, has been completely extirpated, not only from public life, but also from poetry, from private and domestic life, from the few asylums where the other has remained. It was not without consummate skill that the atheistic science and impious philosophy of modern times pronounced their divorce before condemning them to die" (page 96 ).

https://books.google.com/books?id=zRcKTf-_xuIC&pg=PA96&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false).

Montalembert’s disdain for "atheistic science" and "impious philosophy" seems reconstituted in Ungar's prophecy of a new Dark Ages for America with

Man disennobled—brutalized

By popular science—Atheized

Into a smatterer. (Part 4 Canto 21, “Ungar and Rolfe”)

https://books.google.com/books?id=BvRDAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA526&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

Transcribed in editorial notes on “To Winnefred” in Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings, page 572.

Lee, “Therapoetics,” page 96, footnote 28.

Elizabeth Renker, Realist Poetics in American Culture, 1866-1900 (Oxford University Press, 2018) page 136.

See Elizabeth Renker, “Melville the Realist Poet” in A Companion to Herman Melville, edited by Wyn Kelley (Wiley Blackwell, 2006) page 494. In this earlier formulation, Renker assessed Grain by Grain as “Melville’s realist obliteration of the ideal garden”; and paraphrased instead of quoting from The Accepted Time.

Here quoted from “The Encantadas” in Herman Melville, The Piazza Tales (New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856) page 369. Emphasis mine.

Basem L. Ra’ad. “‘The Encantadas’ and ‘The Isle of the Cross’: Melvillean Dubieties, 1853-54.” American Literature 63, no. 2 (1991): 316–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2927169.

Sheet 9v (seq. 18): https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=18 and

Sheet 10 (seq. 19): https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:16083258?n=19

Melville, Herman, 1819-1891. Unpublished poems : autograph manuscript, undated. Herman Melville papers, 1761-1964. MS Am 188 (369.1). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.Folder 1. Weeds and wildings: As they Fell.

“THE AVATAR” immediately precedes “THE ACCEPTED TIME” in the Constable edition of The Works of Herman Melville volume 16 (London, 1924) page 335.