What grand irregular thunder, thought I….

— “The Lightning-Rod Man” (1854)

Hello and welcome to Melvilliana on Substack! My inaugural essay here won’t exactly be child’s play, but it will document some fun and instructive examples of literary plagiarism1 by Herman Melville from one or another version of a popular science guidebook for schoolchildren. For the first time ever? If any sleuth has scooped me anywhere in print or cyberspace I would be glad to know and eager to give due credit. Reader! gentle or not, your comments, corrections, and suggestions are always welcome on Melvilliana. As best I can tell, the homely source-text identified herein has long eluded biographers and critics, and is not down, yet, in any scholarly bibliography of Melville’s Reading or Melville’s Sources. Good! more joy for us awaits, in this our shared experience of discovery. From start to finish, Herman Melville’s short fiction “The Lightning-Rod Man” is electrified by the series of basic questions and answers about thunder and lightning originally presented in the first chapter (Section 2, “Electricity”) of the popular schoolbook by Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, A Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar.

Suggestively classified by historian Bernard Lightman as a “scientific catechism,” Brewer’s influential Guide was first published in 1847 in London by Jarrold and Sons; a second London edition appeared in 1848.2 By January 1851 a cheap reprint of the English edition of Brewer’s Guide was available to American families and schools, issued by C. S. Francis & Co. in New York and J. H. Francis in Boston. Price 62 1⁄2 cents. As in England, the work was commonly known and promoted as “Dr. Brewer’s Guide to Science.” A few months later, Robert Evans Peterson offered a substantively different American edition of Brewer’s Guide entitled Familiar Science; or, The Scientific Explanation of Common Things (Philadelphia, 1851). Peterson’s Familiar Science featured helpful, user-friendly improvements to the ordering and arrangement of information in Brewer’s Guide to Science.3 Evidently a cautious and conscientious editor, Peterson individually numbered each of Brewer’s question-and-answer pairs, printing a total of 1,918 over 530 pages, not counting the index. In places he changed the order of Q/A sets, while lightly revising content and language with his American audience in mind. Brewer approved, endorsing Peterson’s “handsomely printed and skilfully rearranged” edition of his Guide in a letter to the American editor, extracted in the Preface to later printings of Familiar Science. Both titles, in a variety of editions and printings, circulated in New York and Massachusetts when Melville wrote “The Lightning-Rod Man” at his Arrowhead farm place near Pittsfield, most likely in spring or early summer 1854 according to the standard chronology.4

Images below reproduce early, favorable notices of Peterson’s Familiar Science in the New York Spectator for June 26, 1851, via GenealogyBank

and the Boston Evening Transcript for June 28, 1851, via newspapers.com

It may be possible eventually to determine which base-text Melville used, British or American, if not the exact edition. More work is needed on that score, and Melvilliana is here for it. The more detailed and colorfully worded index in Peterson’s edition would doubtless have appealed to Melville, as well as the numbering and more coherent arrangement of questions and answers. For now, simply to document Melville’s extensive debts in “The Lightning-Rod Man,” I will cite the 1852 edition of Peterson’s Familiar Science, conveniently digitized and accessible via Google Books

https://books.google.com/books?id=khguAAAAYAAJ&pg

and HathiTrust Digital Library:

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hnyaux

Inviting comparison and further study, the 1852 “Common School Edition” of Peterson’s Familiar Science is accessible on the great Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/familiarscienceo00pete_0/page/n5/mode/2up

Coincidentally, Peterson’s Familiar Science was reprinted in May 1854, around the time Melville is thought to have composed his short salesman’s story.5

The Lightning-Rod Man first appeared in the August 1854 number of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, on pages 131-134. It was collected with other of Melville’s tales and sketches from Putnam’s, and one new one (“The Piazza”), in The Piazza Tales (New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856), pages 271-285. Melville’s tale unfolds in humorous dialogue between the narrator, a frank and independent sort of mountain philosopher and the eccentric, devilishly determined traveling salesman who visits him during a thunderstorm. Preaching safety first, and the urgency of following the established Science of lightning (however ridiculous or inhumane in practice), the salesman emerges as a figure of oppressive religious and scientific orthodoxy. As a weird mix of predatory clergyman and popular-science expert, Melville’s salesman looks back through allusion to Chaucer’s Pardoner, and forward, prophetically, to Bill Nye the Science Guy. Throw in assorted traits of demon, conjuror, con-artist, and you have him. This being fiction—and a comedy, fortunately—our narrator gets the best of it. In the end, Melville’s noble homeowner righteously (quoting holy writ) and forcibly ejects the lightning-rod man, having heard enough of this salesman’s pitch.

In Melville’s Short Fiction, 1853-1856, William B. Dillingham characterized the narrator’s stand as “heroic defiance.”6 Rightly, I think, although the honorable Emory professor was perhaps too harsh in his judgment of Melville’s jovial homeowner as woefully proud and self-centered. OK, I might ought to have taken more English courses at Emory including his but hey, I was barely 20 then and way more into blues and associated inducements at the Downtown Café than Bartleby or Beowulf….

If you could have seen her

At the Downtown Café

You’d know why I cry

Sing the blues everyday.

Immortalized in The Wiggle (R. I. P. Chicago Bob Nelson), quoted above from memory. Yes indeed! More directly relevant to the matter at hand, tumbling into Melville’s secret source for all that thunder-and-lightning jazz, is Dillingham’s observation of the plain fact that Melville structured “The Lightning-Rod Man” as “a conversation” full of “questions and answers”:

“Melville has created a conversation which serves as a metaphor for his theme of the obsessed rebel against the world. In the course of some eight pages, he includes no less than forty questions, some of them posed by the salesman, some by the narrator. Most of them are answered in one fashion or the other, but despite the great number of questions and answers exchanged between the two men, there is no real communion.”7

Perhaps the conversation itself is the real point. Then, too, conversation implies and usually requires some experience of communion between speaker and listener. In this light Melville’s more philosophical writings might be said to exist largely for the sake of invented dialogue, here as in other “books of talk,” namely Mardi (1849); The Confidence-Man (1857); and Clarel (1876).8 How wonderfully convenient then for Melville when forging his career as magazinist, considering his ingrained habit of pirating the work of others as well as his penchant for dramatization, to have encountered in Peterson’s Familiar Science (or Dr. Brewer’s prior Guide) a compact volume of useful source material already formatted in dialogue.

Dillingham counted "no less than forty questions” in “The Lightning-Rod Man.” Most of them (over two dozen and counting) as shown below, have exact counterparts in Brewer’s original Guide and Peterson’s Familiar Science, formatted in every version as a “scientific catechism” (Bernard Lightman’s term, cited above). As the New World Encyclopedia reminds,

“Catechisms have, historically, typically followed a dialogue or question-and-answer format.” https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Catechism

Countering the narrator’s charges of fear-mongering, superstition-peddling, and fraud, Dillingham calmly defends the accused salesman as “a spokesman for accepted scientific views on lightning.” Faulty science, according to Allen Moore Emery, elevated to a religion by hucksters and paranoid tech wizards.9 Emery proposed writings by Ben Franklin on electricity and Lucius Lyon on lightning-rods in the 1853 Treatise on Lightning Conductors as major influences on “The Lightning-Rod Man.” As will be seen, however, the more immediate source for both the dialogic form and scientific content is some version of Dr. Brewer’s Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar, very possibly the well-received American edition of Peterson’s Familiar Science; or, The Scientific Explanation of Common Things. Nevertheless, Franklin and Lyon should continue to merit attention as relevant analogues, while Emery seems more than vindicated in his prescient argument for worship of flawed Science and the tyranny of experts as intended targets of Melville’s satire. And Dillingham pointed us in the right direction by calling attention to the dialogic structure of Melville’s story, most essentially a conversation developed through a “great number of questions and answers.”

As recognized more recently by Joshua Matthews, the script for the salesman’s part in the dramatized conversation derives from a set of “safety instructions”:

“His performance, intended to produce anxiety in his potential customer, acts out the safety instructions he advises the narrator to take.”10

Yes indeed! The two characters in Melville’s one-act drama “The Lightning-Rod Man,” narrator and salesman, have both been conjured up from some version of Dr. Brewer’s question-and-answer catechism in popular science, along with the form and content of their dialogue. Proofs to follow.

Nuts and bolts of literary plagiarism

The story opens to the “irregular” sound of thunder, effected by neighboring “mountains” that “break and churn up the thunder, so that it is far more glorious here than on the plain.” As presented by Melville, the narrator’s romantic proem rewrites one of Dr. Brewer’s question-and-answer pairs, #126 in Peterson’s Familiar Science. 11

Q. Is not the sound of thunder affected by local circumstances?

A. Yes; the flatter the country the more unbroken the peal. Mountains break the peal and make it harsh and irregular. [page 40]

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hnyaux?urlappend=%3Bseq=46%3Bownerid=27021597767243329-50

Melville keeps the key words mountains, break, and irregular, adds “churn” to vary break, and creatively visualizes the “flatter” landscape first described by Dr. Brewer as an all-American “plain.” The form of “zig-zag irradiations” witnessed by Melville’s narrator is specifically indexed on the last page of Familiar Science. Peterson’s version literally ends with “Zig-zag lightning,” the last index-entry on the last page (558) of the work. In the main body, three consecutive Q/A pairs (27-29, page 15) explain the “zig-zag” course of lighting in terms of “resistance of the air.” A bit later Melville’s narrator hears “a glorious peal” of mountain thunder, introducing a fourth word, peal, lifted from one particular set ( #126) about how mountains affect the sound of thunder.

Soaking wet, the stranger refuses the narrator’s invite to dry out by the fire. Avoiding hearth, the dripping visitor chooses to stand alone “in the exact middle of the cottage.” #74, page 27: “Why is the middle of a room more safe than any other part of it in a thunder storm?”

On closer inspection the ghoulish-looking visitor resembles Edgar Allen Poe in that well-known daguerreotype, although the narrator jokingly addresses him as “that illustrious god Jupiter Tonans.” That is to say, famous Thunderer.

Narrator and guest will fix their physical and metaphorical standpoints in repeated invitations to stand, either by the fire-place for comfort (narrator) or in the middle of the room for safety (guest). Each of Melville’s fictive interlocutors rejects the other’s invitation, more than once. Sticking to the middle of the room, the odd houseguest interrogatively warns his host against the hearth:

"Are you so horridly ignorant, then," he cried, "as not to know, that by far the most dangerous part of a house during such a terrific tempest as this, is the fire-place?"

The visitor’s dire warning against the “fire-place” as the “most dangerous” spot in the house is lifted directly from #58 in Familiar Science:

Q. What parts of a dwelling are most dangerous during a thunder storm?

A. The fire-place, especially if the fire be lighted ; the attics and the cellar. It is also imprudent to sit close by the walls; to ring the bell, or to bar the shutters during a thunder storm. [pages 22-23]

His particular reasons for avoiding the fireplace (“heated air and soot are conductors”) duly follow the guidance given in Familiar Science #59:

Q. Why is it dangerous to sit before a fire during a thunder storm?

A. Because the heated air and soot are conductors of lightning; especially when connected with such excellent conductors as the stove, grate, or fire-irons. [page 23]

Except that in the rewrite, Melville refashions the non-descript “fire-irons” of #59 into “immense fire-dogs.”

Tragic events in Criggan and Montreal, exemplifying real-world failures of lightning rods to protect people and property in severe weather, seem to be made-up or adapted from other sources. The closest parallel in Familiar Science occurs in #103, page 34, on the near destruction of St. Bride’s Church, London in the 18th century. But the excuses offered by the narrator’s eccentric guest, having disclosed his business as itinerant “dealer in lightning-rods,” come straight out of Familiar Science on the best kind of “lightning conductor,” specifically #80 and #81:

Q. What metal is best for this purpose ?

A. Copper makes the best conductor.Q. Why is copper better than iron?

A. 1st.—Because copper is a better conductor than iron; 2nd.—It is not so easily fused or melted; and 3rd.—It is not so readily injured by weather. [pages 28-29]

On the defensive, Melville’s vendor blames the Montreal disaster on the use of inferior “iron rods” in Canada: “They should have mine, which are copper. Iron is easily fused.” The superiority of copper, being “not so easily fused,” over iron in the manufacture of lightning rods is the main point of Q and A pairs #80 and #81 in Familiar Science. The next pair, #82, affirms the virtue of “pointed” lightning-conductors rather than ones with “knobs”:

Q. Why should lightning-conductors be pointed?

A. Because points conduct electricity away silently and imperceptibly; but knobs produce an explosion which would endanger the building. [page 29]

#82 is Melville’s source for the science behind the salesman’s allegation that incompetent Canadians “knob the rod at the top, which risks a deadly explosion, instead of imperceptibly carrying down the current into the earth.” The key words knob, explosion, and imperceptibly all derive from Familiar Science #82.

Subsequently Melville’s narrator catches the traveling salesman taking his own pulse. The low number of beats (“only three pulses”) between the observed “flash” of lightning and the next “Crash!” of thunder confirms the dangerous proximity of the storm, “less than a third of a mile off.” This sudden, striking (and to some critics, absurd) physical action of pulse-taking has been concretely visualized from the source-text in #124, where Dr. Brewer in Peterson’s edition of Familiar Science explains how to calculate distance from a storm by measuring your heart rate.

A popular method of telling how far off a storm is, is this—The moment you see the flash put your hand upon your pulse, and count how many times it beats before you hear the thunder; if it beats six pulsations, the storm is one mile off; if twelve pulsations, it is two miles off, and so on. [page 40]

According to Familiar Science, three beats means half a mile. But Melville’s panicky salesman exaggerates, making the storm even closer than Dr. Brewer’s method technically would allow, “less than a third of a mile off” in a nearby forest. Implying he had just walked through these same woods, the lightning-rod dealer claims to have “passed three stricken oaks there, ripped out new and glittering.” (Glittering! The adjective glittering belongs to Melville’s working vocabulary of revision, as I discovered in a previous investigation.) Without prompting the salesman then accounts for the awful downfall of three “new and glittering” oak trees in scientific terms: “The oak draws lightning more than other timber, having iron solution in its sap.” Here again the elementary science derives from Familiar Science, borrowed without credit from Q and A pair #92:

Q. Why is an oak struck by lightning more frequently than any other tree?

A. Because the grain of the oak, being closer than that of any other tree of the same bulk, renders it a better conductor.

It is said that the sap of the oak contains a large quantity of iron in solution, which impregnates the wood and bark, thus increasing its conducting power. [page 31]

Melville’s rewrite skips over the main part of the answer about the oak being more densely grained than other kinds of trees, and uses instead the casual observation after, that the “sap” of oak trees contains “iron in solution” (compressed to “iron solution”).

Some of the more interesting physical actions depicted in Melville’s narrative are developed from his source-text in Familiar Science. One example is the peddler’s sudden pulse-taking, documented above. Another is the imaginary act, intended but not carried out by the narrator, of closing window shutters and using a bar to secure them.

Yet first let me close yonder shutters; the slanting rain is beating through the sash. I will bar up.”

“ Are you mad ? Know you not that yon iron bar is a swift conductor? Desist."

“I will simply close the shutters, then, and call my boy to bring me a wooden bar.

Along with the thunderstorm, shutters and bar also derive from Familiar Science #63:

Q. Why is it dangerous to bar a shutter during a thunder storm?

A. Because the iron shutter-bar is an excellent conductor; and the electric fluid might run from the bar through the person touching it, and injure him. [page 24]

Melville’s “yon” makes Dr. Brewer’s iron bar visibly real, when thus placed in the sightline of his fictive narrator. Instead of Brewer’s adjective excellent, Melville chooses “swift” to modify “conductor.”

The supposed need for a shutter-bar made of wood requires a boy, and a bell. That is, a servant “boy” to bring the wooden bar, and a bell with which to call the boy.

Pray, touch the bell-pull there."

“ Are you frantic? That bell-wire might blast you. Never touch bell-wire in a thunderstorm, nor ring a bell of any sort."

Melville invents the boy but kipes the bell, more precisely the bell-wire, from Dr. Brewer’s catechism, #62 in Familiar Science:

Q. Why is it dangerous to ring a bell during a thunder storm?

A. Bell-wire is an excellent conductor, and if a person were to touch the bell handle, the electric fluid, passing down the wire, might run through his hand and injure it. [pages 23-24]

The salesman’s negative, melodramatic reaction to the very idea of pulling a bell in rough weather makes the narrator wonder if even church-bells (“those in belfries”) must be treated as too risky to ring. Yes, according to the catechism in Familiar Science, #56:

Q. Why is it dangerous to ring church bells during a thunder storm?

A. For two reasons; 1st. Because the steeple may discharge the lightning-cloud merely from its height; and 2nd.—As the swinging of the bells puts the air in motion, it diminishes its resistance to the electric fluid. [page 22]

Before we leave this particular revision site 12, witnessing the rewrite of #56, I want to notice and appreciate the fun Melville wrung here from Brewer’s catechism of juvenile science. Are you frantic? Hahaha!

Are you insane? is what the salesman means, employing frantic in the old sense of “mad” i.e. “crazy.” Webster in 1853 defined frantic as “Mad; raving; furious; outrageous; raging; desperate; wild and disorderly; distracted.” Hilarious, literally a line from Seinfeld. And dramatically ironic, since discerning readers by now have perceived Melville’s salesman as the frantic one, extremely fearful and anxious if not mentally disturbed.

That bell-wire might blast you. Glorious! Melville came up with his own b-word, blast, to alliterate with the one he appropriated from his source-text, bell-wire. Melville’s “blast” verbally echoes “bell-wire” through alliteration, and “frantic” through assonance. File this example for future reference. The use of alliteration and assonance for pleasing and poetic effects may turn out to be a regular feature in the mechanics of Melville’s rewriting.

The “returning stroke”

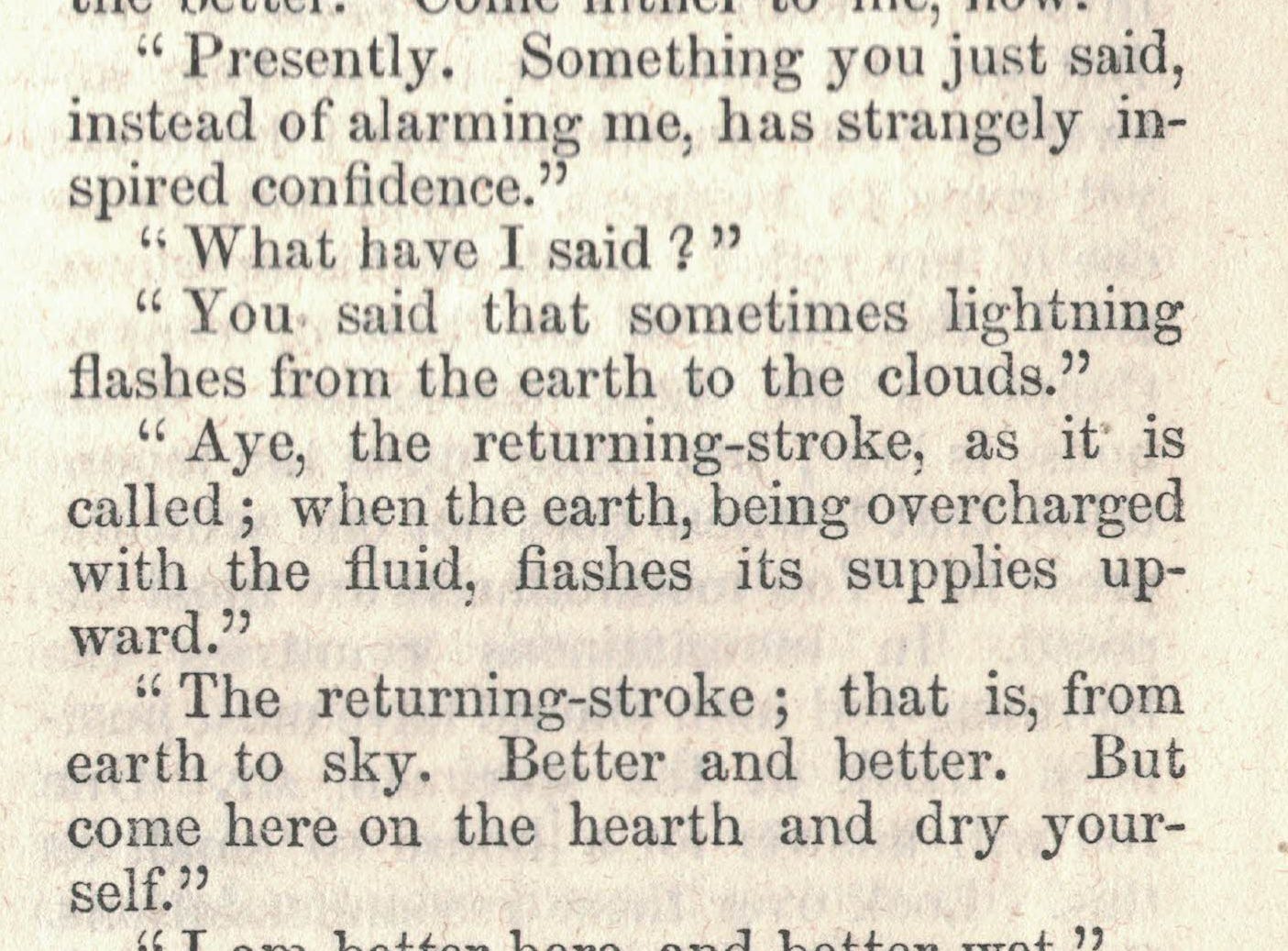

"You said that sometimes lightning flashes from the earth to the clouds."

"Aye, the returning-stroke, as it is called; when the earth, being overcharged with the fluid, flashes its surplus upward." — The Lightning-Rod Man

As emphasized in the best academic criticism on “The Lightning-Rod Man,” the narrator exhibits extra-significant curiosity about the “returning-stroke” of lightning from earth to sky. Melville’s highly agitated salesman—nervous and fearful yet aggressively persistent in his not taking “NO” for an answer—won’t get the point of that interest until the end of the story when the narrator throws him out of the house. Until then, the eccentric guest ignores the threat of physical violence implicit in his host’s special fascination with “the returning-stroke.” As metaphor, the returning-stroke could represent the narrator’s Ahab-like “heroic defiance” of orthodoxy (as Dillingham would have it), or the God-given spark of divinity in each human being. Whatever it means, you can safely say the lightning-rod dealer took his host’s kindness for weakness.

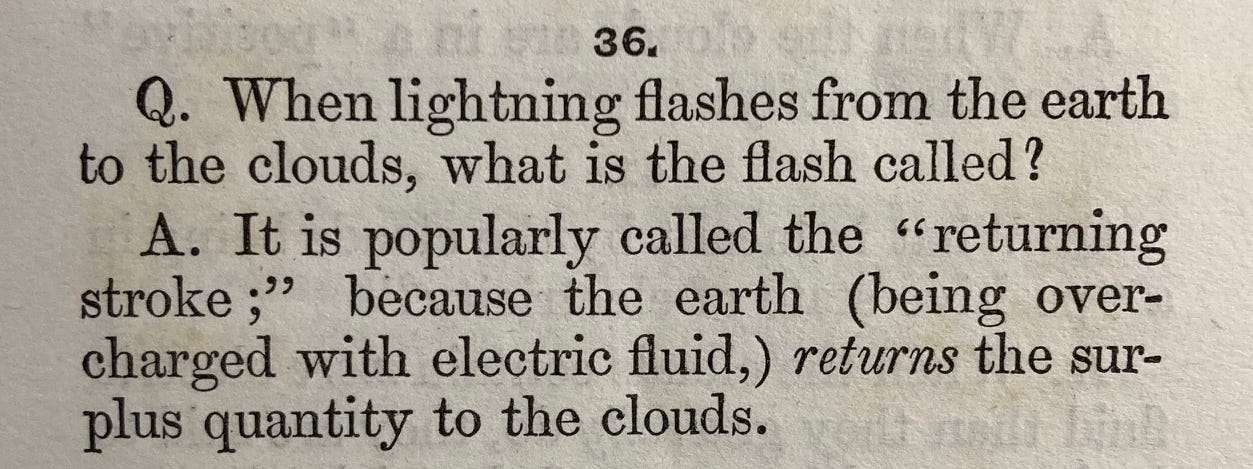

You can also say with absolute certainty that Melville appropriated essential elements in the conversation about “the returning-stroke” from a printed source, either Dr. Brewer’s Guide or Q and A #36 in Peterson’s Familiar Science:

Q. When lightning flashes from the earth to the clouds, what is the flash called?

A. It is popularly called the “returning stroke;" because the earth (being overcharged with electric fluid,) returns the surplus quantity to the clouds. [page 17]

Here Melville’s rewrite is especially faithful to the original wording of his source-text. Melville has copied it verbatim, in places:

Familiar Science #36 lightning flashes from the earth to the clouds

Lightning-Rod Man: lightning flashes from the earth to the clouds

Familiar Science #36 the earth (being overcharged with electric fluid

Lightning-Rod Man: the earth, being overcharged with the fluid,

Familiar Science #36: returns the surplus quantity to the clouds

Lightning-Rod Man: flashes its surplus upward

The boldness of borrowing here is remarkable, even for a habitual plagiarist like Melville. Brazenly, he imports big chunks of stolen text without bothering to disguise the theft. Along with his telling re-use of “returning stroke,” Melville also hijacked single words from Familiar Science, the verb flashes and noun surplus, and conjoined them in the phrase “flashes its surplus” (“supplies” in the original magazine version, page 133, emended to “surplus” in The Piazza Tales, page 281). Where his source is redundant, Melville compresses. The answer to #36 in Familiar Science repeats part of the question: “to the clouds.” Melville avoids needless repetition through revision, avoiding a second instance of the phrase to the clouds by substituting “upward” instead.

Most of the peddler’s remaining pointers on staying safe in a thunderstorm likewise originate in Dr. Brewer’s catechism (very likely as rearranged in Peterson’s American version) on the basic science of thunder and lightning. Full documentation will be provided in part 2 of the present essay, again with reference throughout to Peterson’s 1852 edition of Familiar Science.

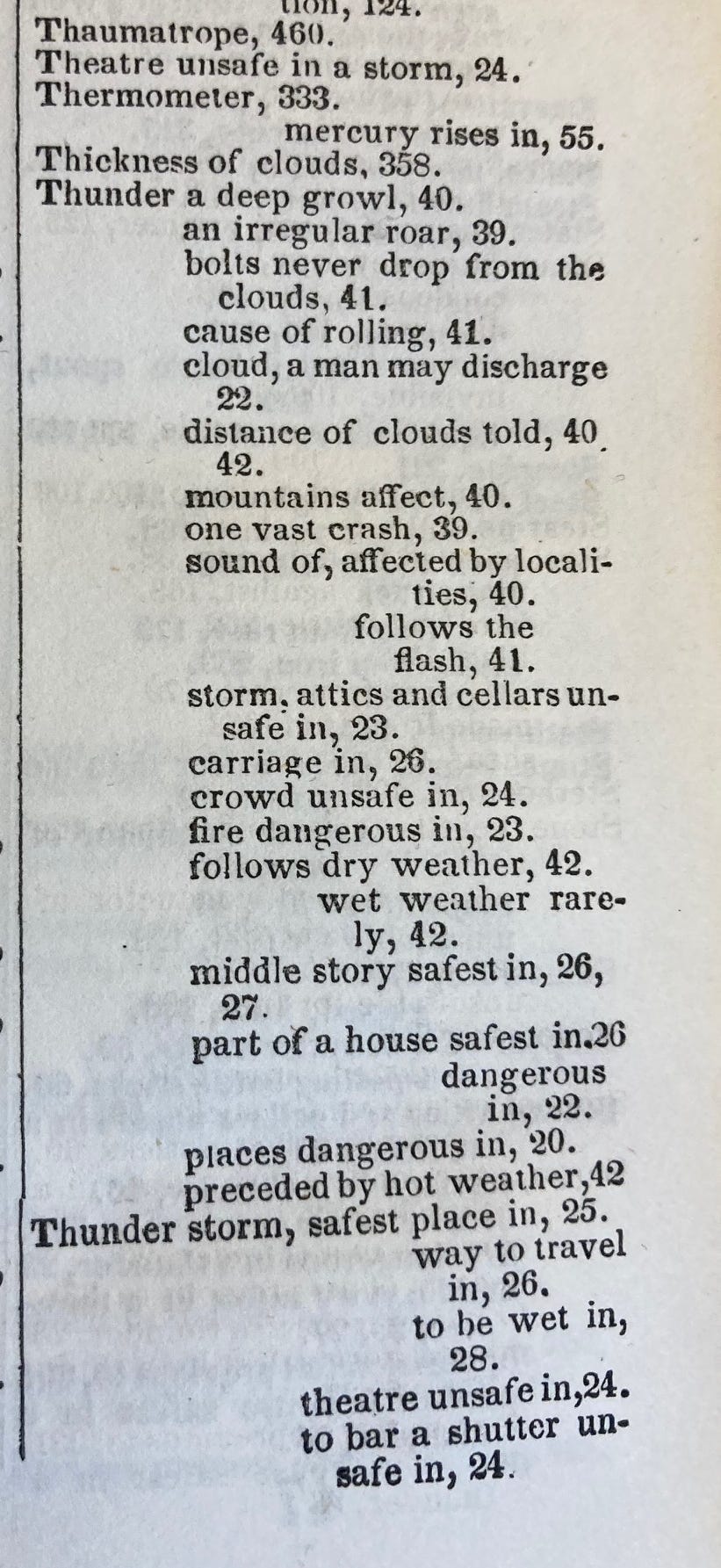

Above, entries for “Thunder” listed in the Index to Peterson’s Familiar Science, page 554. This ends part 1 of Borrowed Thunder. Part 2 coming soon!

Footnotes below, after the break…

Marilyn Randall usefully explicates the term literary plagiarism as “copying that achieves a superior level of aesthetic approval” and “a kind of pleasing oxymoron expressing the transformative power of aesthetic genius” in Pragmatic Plagiarism: Authorship, Profit, and Power (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001) pages 3 and 6.

Bernard Lightman, Victorian Popularizers of Science: Designing Nature for New Audiences (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2007) pages 66-67.

Google-digitized versions of Peterson’s Familiar Science are accessible online courtesy of HathiTrust Digital Library, including scanned copies of physical volumes at Harvard University (Philadelphia, 1852) and the New York Public Library (Philadelphia, 1854). https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008630095

HathiTrust also has digitized copies of Brewer’s Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar in the American edition published by C. S. Francis & Co. and J. H. Francis (New York and Boston, 1852), scanned from physical volumes at the University of Virginia, University of California, and Harvard. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007356240

Merton M. Sealts, Jr., “Chronology of the Short Fiction” in Pursuing Melville, 1940-1980 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982) pages 221-231 at 228; also incorporated in The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860, ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, G. Thomas Tanselle, and others (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 1987) page 493.

Hershel Parker first identified the genre in "Melville's Salesman Story," Studies in Short Fiction (Winter 1964) pages 154-158. Parker discounted interpretations of “the lightning rod as a symbol of modern (and meretricious) science,” instead taking the demonic imagery and scriptural allusions as features of Melville’s satirical “attack on American evangelical Protestantism” (155).

William B. Dillingham, Melville's Short Fiction, 1853-1856 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1977) page 175.

Dillingham, page 181. Emphasis added.

John Paul Wenke calls Mardi “Melville’s first book of talk” in Melville's Muse: Literary Creation and the Forms of Philosophical Fiction (Kent State University Press, 1995) page 48.

Allan Moore Emery, “Melville on Science: ‘The Lightning-Rod Man.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 4, New England Quarterly, Inc., 1983, pp. 555–68, https://doi.org/10.2307/365105. For a really good, recent exploration of Emery’s theme, see Tobin L. Craig, “Technology and anxiety in Melville's ‘Lightning-Rod Man,’ in Science fiction and political philosophy : from Bacon to Black Mirror, ed. Steven Michels and Timothy McCranor (Lexington Books, 2020).

Joshua Matthews, "Peddlers of the Rod: Melville's "The Lightning-Rod Man" and the Antebellum Periodical Market." Leviathan, vol. 12 no. 3, 2010, p. 55-70. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492986.

For easy reference and fact-checking, Melville’s source-text here and throughout is quoted from the American version of Dr. Brewer’s questions and answers, as numbered and occasionally rearranged in Familiar Science; or, The Scientific Explanation of Common Things, edited by Robert Evans Peterson (Philadelphia, 1852).

For the super-useful term revision site I am indebted to John Bryant; see for example Melville Unfolding: Sexuality, Politics, and the Versions of Typee (University of Michigan Press, 2008) page 29. https://www.press.umich.edu/183647/melville_unfolding

Who knew??!

Now I do. Many thanks.