Sweeping up

Part 1 documented some of Herman Melville’s extensive literary debts in The Lightning-Rod Man to one or another version of Ebenezer Cobham Brewer’s Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar, perhaps the improved American edition issued by Robert Evans Peterson, Familiar Science; or, The Scientific Explanation of Common Things (Philadelphia, 1851). As discussed near the conclusion of part 1, one of the more notable instances of creative plagiarism concerns the "returning stroke" of lighting from earth to sky, a phenomenon that fascinates Melville’s narrator. Information about the “returning stroke” provided by the lightning-rod salesman comes directly from Melville’s source text, presented as question-and-answer #36 in Peterson’s Familiar Science. Here as elsewhere in “The Lightning-Rod Man,” Melville’s imaginative re-write closely follows the language of his source-text, in places word-for-word.

Nearly all of the pro tips on staying safe in a thunderstorm likewise derive from questions and answers about thunder and lightning that originated in Dr. Brewer’s scientific catechism. Melville’s reliance for the salesman’s expert advice on some version of Brewer’s guide to the Science of Familiar Things is documented below, with links to the digitized 1852 volume of Peterson’s Familiar Science at Google Books:

Below, page 23 in Peterson’s Familiar Science, 1852 edition, with Q and A numbers 59-61—all adapted by Melville in The Lightning-Rod Man.

Walls

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133 in Putnam’s magazine, col. 1

”Come away from the wall. The current will sometimes run down a wall, and—a man being a better conductor than a wall—it would leave the wall and run into him.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #61 - page 23.

Q. Why is it dangerous to lean against a wall during a thunder storm?

A. Because the electric fluid will sometimes run down a wall; and, (as a man is a better conductor than a wall,) would leave the wall and run down the man.

Globular lightning

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 1

”Swoop! That must have fallen very nigh. That must have been globular lightning.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #32 - page 16

Q. What other form does lightning occasionally assume?A. Sometimes the flash is globular; which is the most dangerous form of lightning.

Middle story safest

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

”Your house is a one-storied house, with an attic and a cellar; this room is between. Hence its comparative safety. Because lightning sometimes passes from the clouds to the earth, and sometimes from the earth to the clouds. Do you comprehend?”

FAMILIAR SCIENCE # 60 - page 23 (shown above)

Q. Why are attics and cellars more dangerous in a thunder storm, than the middle story of a house?

A. Because lightning sometimes passes from the clouds to the earth, and sometimes from the earth to the clouds; in either case the middle story would be the safest place.

Better wet.

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

”I am better here, and better wet.” … “Wet clothes are better conductors than the body; and so, if the lightning strike, it might pass down the wet clothes without touching the body.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #77 and #78 - page 28

77.

Q. Is it better to be wet or dry during a thunder storm?

A. To be wet; if a person be in the open field, the best thing he can do, is to stand about twenty feet from some tree, and get completely drenched to the skin.

78.

Q. Why is it better to be wet than dry?A. Because wet clothes form a better conductor than the fluids of our body; and therefore, lightning would pass down our wet clothes, without touching our body at all.

Rugs.

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

”Rugs are non-conductors.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #75 - page 27

Q. Why is a mattrass, bed, or hearth-rug, a good security against injury from lightning?A. Because they are all non-conductors ; and, as lightning always makes choice of the best conductors, it would not choose for its path such things as these.

Safety precautions, summarized.

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

"… let me hear your precautions in traveling during thunder-storms." "Briefly, then. I avoid pine-trees, high houses, lonely barns, upland pastures, running water, flocks of cattle and sheep, a crowd of men.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #51 - page 20

Q. What places are most dangerous during a thunder storm?

A. It is very dangerous to be near a tree, or lofty building; and also to be near a river, or any running water.

Flocks, cattle and sheep

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

"Briefly, then. I avoid pine-trees, high houses, lonely barns, upland pastures, running water, flocks of cattle and sheep, a crowd of men” [emphasis added].

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #67 - page 25

Q. Why is a flock of sheep, herd of cattle, etc., in greater danger than a smaller number?A. 1st.-Because each animal is a conductor of lightning, and the conducting power of the flock or herd, is increased

by its numbers; and

2nd.—The very vapor arising from the flock or herd increases its conducting power and its danger.

Crowds

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 133, col. 2

"Briefly, then. I avoid pine-trees, high houses, lonely barns, upland pastures, running water, flocks of cattle and sheep, a crowd of men.” [emphasis added]

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #64 - page 24. See also #65 and #66.Q. Why is it dangerous to be in a crowd during a thunder storm?

A. For two reasons: Because a mass of people forms a better conductor than an individual; and 2nd.—Because the vapor arising from a crowd increases its conducting power.

Safe traveling

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - pages 133-4

If I travel on foot -- as today -- I do not walk fast; if in my buggy, I touch not its back or sides; if on horseback, I dismount and lead the horse.FAMILIAR SCIENCE #70 - page 26

Q. If a person be in a carriage in a thunder storm, in what way can he travel most safely?A. He should not lean against the carriage, but sit upright, without touching any of the four sides.

Tall men

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 134 in Putnam’s magazine, col. 1

"Tall men in a thunder-storm I avoid. Are you so grossly ignorant as not to know, that the height of a six-footer is sufficient to discharge an electric cloud upon him? Are not lonely Kentuckians, ploughing, smit in the unfinished furrow? Nay, if the six-footer stand by running water, the cloud will sometimes select him as its conductor to that running water.”FAMILIAR SCIENCE # 55 - pages 21-22

Q. Why is it dangerous for a man to be near water in a thunder storm?A. Because the height of a man may be sufficient to discharge a cloud; and (if there were no taller object nigh) the lightning might make the man its conductor to the water.

Man is a good conductor.

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 134, col. 1

”Yes, a man is a good conductor. The lightning goes through and through a man, but only peels a tree.”

FAMILIAR SCIENCE INDEX

"Man better conductor than a tree, 33.” Index - page 547.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #98 - PAGE 33

Q. Why would lightning fly from a tree or spire into a man standing near?A. Because the electric fluid (called lightning) always chooses for its path the best conductors; and, if the human fluids proved the better conductor, it would

pass through the man standing near the tree, rather than down the tree itself.

Peels a tree

FAMILIAR SCIENCE INDEX

"Tree, bark of, torn by lightning, 33.” Index - page 555.FAMILIAR SCIENCE #101 - PAGES 33-34

Q. Why is the bark of a tree often ripped quite off by a flash of lightning?

A. Because the latent heat of the tree (being very rapidly developed by the electric fluid) forces away the bark in its impetuosity to escape.

Some part of this is probably due to the simple mechanical force of the lightning.

Efficacy of lightning rod

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 134, col. 1

”An elevation of five feet above the house will protect twenty feet radius all about the rod.”

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #84 and #85 - pages 29-30.

84.

Q. How far will the beneficial influence of a lightning-conductor extend ?A. It will protect a space all round, four times the length of that part of the rod, which rises above the building.

85.

Q. Give me an example?

A. If the rod rise two feet above the house, it will protect the building for (at least) eight feet all round.

At the dramatic climax of Melville’s tale, even the narrator takes his cues from Dr. Brewer’s Guide to Science. Specifically, his image of “light from the Leyden jar” and closing invocation of scripture, both deployed to denounce the salesman as a charlatan, have direct parallels in all editions and printings, including Peterson’s Familiar Science.

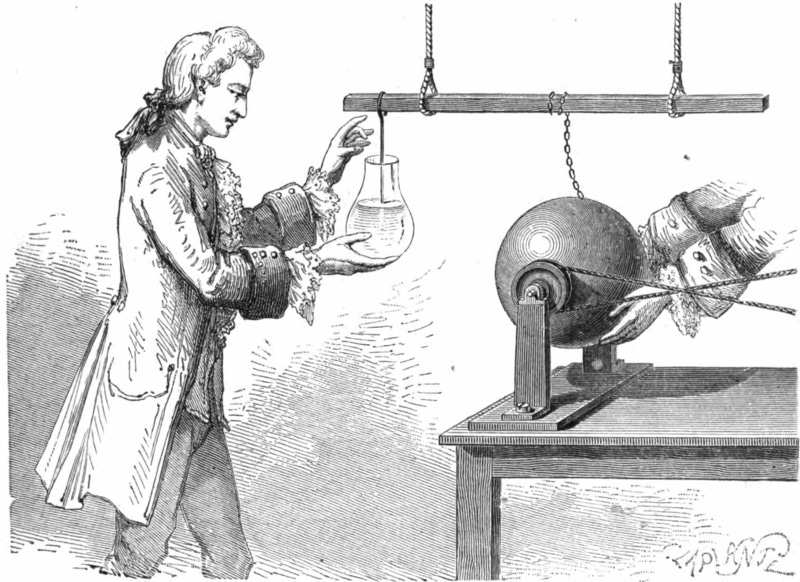

Leyden jar

LIGHTNING-ROD MAN - page 134, col. 2

”do you think that because you can strike a bit of green light from the Leyden jar, that you can thoroughly avert the supernal bolt?”FAMILIAR SCIENCE #21 - page 13. Also referenced in note to #83 at page 29.

SECTION II.-LIGHTNING.21.

Q. What is lightning ?

A. Lightning is accumulated electricity discharged from the clouds.

Like that from a “Leyden jar.”

As pointedly foreshadowed, Melville’s narrator delivers a loud and lightning-fast “returning stroke” back at the peddler. In a blast of Protestant or faux-Protestant fury, he likens the lightning-rod man to Johann Tetzel, notorious for peddling indulgences, outraging Luther and thereby kicking off the Reformation. Several passages from the Bible are cited as authority for the narrator’s stand against living in fear, including a paraphrase of Jesus’ words in Matthew 10:30 and Luke 12:7:

Who has empowered you, you Tetzel, to peddle round your indulgences from divine ordinations? The hairs of our heads are numbered, and the days of our lives. In thunder as in sunshine, I stand at ease in the hands of my God.

Dr. Brewer anticipated Melville’s narrator in quoting the same New Testament scripture as a crucial element in planning for safety during severe weather. Reasonable precautions recommended in Brewer’s Guide and Peterson’s Familiar Science do not include lighting rods. Rather, # 86 in Familiar Science cautions that “broken” lightning-conductors are “productive of harm”; while #87 identifies another “evil” case “if the rod be not large enough to conduct the whole current to the earth, the lightning will fuse the metal, and injure the building” (page 30).

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #76 - page 27.

Q. What is the safest thing a person can do to avoid injury from lightning?

A. He should draw his bedstead into the middle of his room, commit himself to the care of God, and go to bed; remembering that our Lord has said, “The very hairs of your head are all numbered.”

No great danger need really to be apprehended from lightning, if you avoid taking your position near tall trees, spires, or other elevated objects.

The lightning-rod man is rebuked in the end as a modern inquisitor, a fake, and a fear monger. Finally the narrator casts him out, generally the approved treatment of a demon: “False negotiator, away!” Belief in salvation through science, or scientism, figured in the “tri-forked” rod, stands condemned as the real blasphemy. Experts say, trusting with confidence in God, not lightning rods, is actually one of the safest things you can do in a thunderstorm. Who knew? In echoing the best familiar science, Melville’s narrator effectually takes the salesman’s own prompt book on danger from lightning and reads it back to him, with a vengeance.

Although newly discovered, the large debt to familiar science in “The Lightning-Rod Man” tends to corroborate the real merit of any critical reading, old or new, that allows plenty of sea room for a philosopher and truth-teller who can satirize abuses of human rights by tyrants of Science as well as Religion. In Clarel, a poem and pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876), another dialogue-motivated “book of talk,” Melville would indulge a blunter and bitterer vent against the cult of familiar science in the prophecy uttered by Ungar, the far-wandering army vet. Ungar directly blames “popular science” for the debasement of human dignity, spirit, and culture he foresees:

“Myriads playing pygmy parts— Debased into equality : In glut of all material arts A civic barbarism may be: Man disennobled—brutalized By popular science—Atheized Into a smatterer———” [Book 3, Bethlehem, Canto 21, Ungar and Rolfe]

Of interpretive takes on “The Lightning-Rod Man” that admit faith in science and its more zealous practitioners as legitimate objects of comedy, two of the freshest are now a round fifty years old:

Superficially, we are given a conflict between a comic swindler and a genial but firm homeowner; but on another level, this same opposition satirizes the gadgetry of civilization with the contrast between the sharp, ironic wit of the narrator and the scientific pitch of the salesman.1

The “religion” of Melville’s satanic salesman, then, is scientism; God, for him, is the lightning rod itself and the “security” and “omnipotence” it seems to offer the “modern” man whose fears he seeks to exploit.2

As evident in his manuscript notes from Thomas Roscoe’s German Novelists, Melville was already prone to refashion another writer’s narrative prose into a comical dialogue of his own invention.3 Here in “The Lightning-Rod Man,” however, his source-text for the established science of familiar things was already gift-wrapped in the form of a dialogue between student and teacher. Convenient! and almost too easy for Melville, veteran re-writer that he was, to incorporate a model student’s questions about lightning and the teacher’s answers into a one-act with two speaking parts, mountain philosopher and traveling salesman.

Being so extensive and obvious (once discovered), Melville’s word-for-word copying provides numerous examples of interesting revision sites. Here as in so many other writings by the author of Typee, Omoo, etc., a closer look at Melville’s mechanics, the “nuts and bolts” of revision, can illuminate specific elements of Melville’s process and techniques of rewriting from sources. Hopefully the identification and preliminary discussion of a long unrecognized source for “The Lightning-Rod Man” will contribute to a better understanding and enjoyment of the way Melville habitually made art—the best of which reveals, as Steven Olsen-Smith has found,

the humane orientation of his philosophical and religious sensibilities, and the depth of his appropriative genius.4

I have exciting news to share: You can now read Melvilliana in the new Substack app for iPhone.

With the app, you’ll have a dedicated Inbox for my Substack and any others you subscribe to. New posts will never get lost in your email filters, or stuck in spam. Longer posts will never cut-off by your email app. Comments and rich media will all work seamlessly. Overall, it’s a big upgrade to the reading experience.

The Substack app is currently available for iOS. If you don’t have an Apple device, you can join the Android waitlist here.

Alan Shusterman, "Melville's ‘The Lightning-Rod Man’: A Reading." Studies in Short Fiction 9, no. 2 (Spring, 1972) pages 165-174. For Science as Melville’s main target, see the groundbreaking essay by Allan Moore Emery, “Melville on Science: ‘The Lightning-Rod Man.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 4, New England Quarterly, Inc., 1983, pp. 555–68, https://doi.org/10.2307/365105.

Thomas Werge, “Melville’s Satanic Salesman: Scientism and Puritanism in ‘The Lightning-Rod Man.’” Newsletter of the Conference on Christianity and Literature, vol. 21, no. 3, Sage Publications, Ltd., 1972, pp. 6–12, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26374952.

Scott Norsworthy, "Melville's Notes from Thomas Roscoe's The German Novelists." Leviathan, vol. 10 no. 3, 2008, p. 7-37. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492876.

Steven Olsen-Smith, “The Hymn in Moby-Dick: Melville's Adaptation of ‘Psalm 18,’” Leviathan vol. 5 no. 1, March 2003, pages 29-47 at 47. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/492710.

Scott nailed a Melville source. It proves that a Melville source may be an ordinary household publication.