Blessings of snow and bad ventilation

Documenting Melville's debts to familiar science in "Poor Man's Pudding" (1854)

As shown in my Substack debut Borrowed Thunder, followed up by Borrowed Thunder part 2, Herman Melville’s 1854 short story “The Lightning-Rod Man” is heavily indebted to some version of E. C. Brewer’s popular Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar, possibly the American reprint as expanded and rearranged by R. E. Peterson in Peterson’s Familiar Science (Philadelphia, 1851). Here I want to clinch Melville’s use of the same source in “Poor Man’s Pudding, another piece of magazine fiction published in 1854 and very likely composed before “The Lightning-Rod Man.”1 “Poor Man’s Pudding” is the first of two paired sketches or verbal “Pictures” that appeared in the June 1854 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine under the title, “Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs.”

The pudding in Poor Man’s Pudding is a humble blend of rice, milk, and salt recommended to the narrator by his poet-friend Blandmour. On his friend’s advice the narrator visits a hard-working tenant farmer named Coulter and his pregnant wife who live and suffer together in rural poverty. Earlier Blandmour had glossed over the reality of miserable living conditions experienced by the poor with pleasant talk about the benefits of water and other natural elements, freely dispensed to all by “the blessed almoner, Nature.” First, readers get Blandmour’s rosy picture of providential blessings like snow (“Poor Man’s Manure”) and rain-water (“Poor Man’s Egg”), then the hard facts of life as experienced by William and Martha Coulter. Besides the cold rooms, bare walls, damp window-sills, soggy firewood and rotten food, the Coulters must endure “fathomless” grief over the deaths of two children.

Earth nourished by snow

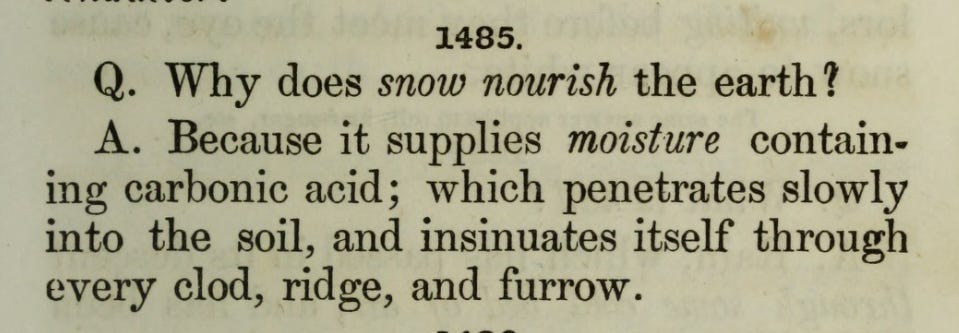

The first paragraph of “Poor Man’s Pudding” contains strong textual evidence that Melville already had some version of Dr. Brewer’s guide to familiar science handy when writing it. Blandmour’s information about the beneficial effects of snow (dubbed “Poor Man’s Manure”) on farmland closely matches question-and-answer #1485 in Peterson’s Familiar Science, page 397:

Q. Why does snow nourish the earth?

A. Because it supplies moisture containing carbonic acid; which penetrates slowly into the soil, and insinuates itself through every clod, ridge, and furrow.

MELVILLE - POOR MAN’S PUDDING - page 95 in Harper’s magazine

Rightly is this soft March snow, falling just before seedtime, rightly it is called ‘Poor Man’s Manure.’ Distilling from kind heaven upon the soil, by a gentle penetration it nourishes every clod, ridge, and furrow.

Melville did not get the proverbial term “Poor Man’s Manure” from any version of Brewer’s Guide to Science, but he did find and use forms of the key words nourish and penetrates. (And moisture, perhaps, picked up in the first sentence of the story where Melville sets the scene as “soft, moist snowfall.”) According to Dr. Brewer, fallen snow helps fertilize or “nourish” the land with moisture that “penetrates slowly,” releasing carbonic acid into the soil. Melville creatively renders the fertilizing action of snow as a heavenly “distilling” and “gentle penetration” that “nourishes every clod, ridge, and furrow” of earth. Most telling is Melville’s phrase “every clod, ridge and furrow,” borrowed verbatim from #1482 in Familiar Science.

Recall “the words of the Psalmist”?

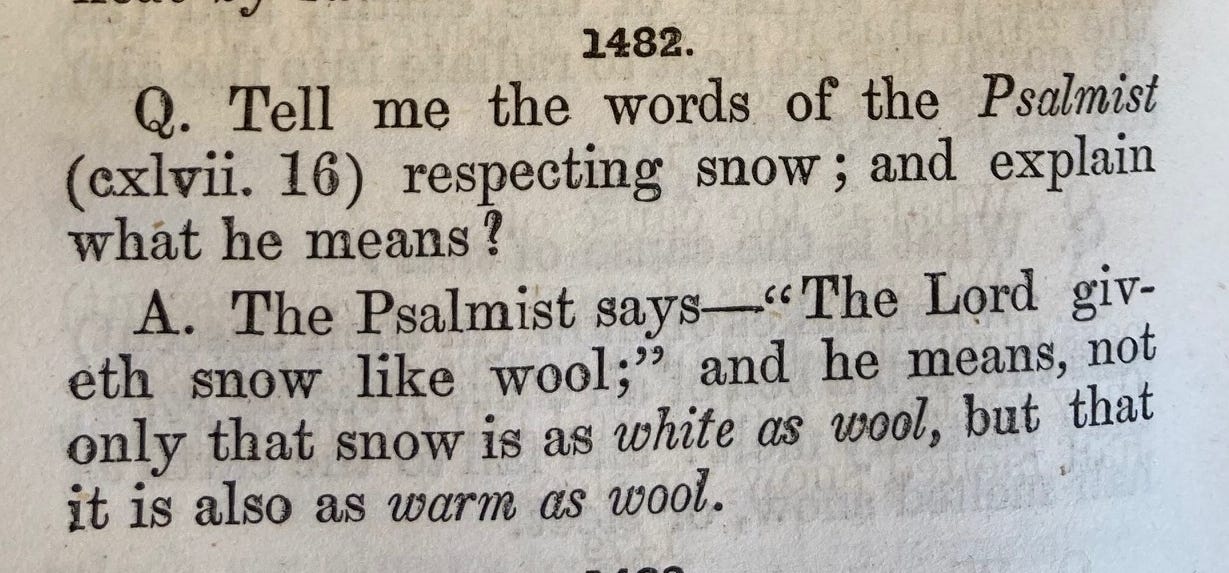

Further along in the conversation that begins “Poor Man’s Pudding,” Blandmour asks a question straight out of Brewer’s scientific catechism.2 Blandmour’s challenge to recall “the words of the Psalmist” about the blessing of snow reproduces both the interrogative format and scriptural content of #1482 in Peterson’s Familiar Science, page 396.

Q. Tell me the words of the Psalmist (cxlvii. 16) respecting snow; and explain what he means ?

A. The Psalmist says— “The Lord giveth snow like wool;” and he means, not only that snow is as white as wool, but that it is also as warm as wool.

MELVILLE - POOR MAN’S PUDDING - page 95 in Harper’s magazine

“Why, do you not remember the words of the Psalmist?—’The Lord giveth snow like wool;’ meaning not only that snow is white as wool, but warm, too, as wool. For the only reason, as I take it, that wool is comfortable, is because air is entangled, and therefore warmed among its fibres. Just so, then take the temperature of a December field when covered with this snow-fleece, and you will no doubt find it several degrees above that of the air. So, you see, the winter’s snow itself is beneficent; under the pretense of frost—a sort of gruff philanthropist—actually warming the earth, which afterward is to be fertilizingly moistened by these gentle flakes of March.”

Melville has appropriated the form of the question, as question, from some version of Familiar Science, as well as the biblical quotation from Psalm 147.16. Blandmour’s “do you not remember” creatively restates the implied science instructor’s demand to “tell me.” Melville then copies the phrase “words of the Psalmist” and the biblical text verbatim. Impressively, having asked Dr. Brewer’s question in #1482 of Familiar Science, Blandmour goes on to give Dr. Brewer’s answer, word-for word.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1482

… he means, not only that snow is as white as wool, but that it is also as warm as wool.

MELVILLE’S BLANDMOUR IN POOR MAN’S PUDDING

… meaning not only that snow is white as wool, but warm, too, as wool.

Warmed by snow

Blandmour’s further explanation of the reason that wool and snow are both warm incorporates other, related Q-and-A sets from the same section on “Rain, Snow, Hail” in Dr. Brewer’s catechism, specifically #1483 and #1484 in Familiar Science, pages 396-397.

1483.

Q. Why is wool warm?A. Because air is entangled among the fibres of the wool; and air is a very bad conductor.

1484.

Q. Why is snow warm?A. Because air is entangled among the crystals of the snow; and air is a very bad conductor.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1483

Because air is entangled among the fibres of the wool; and air is a very bad conductor.

BLANDMOUR

… because air is entangled, and therefore warmed among its fibres.

Blandmour’s information that “air is entangled” in or more precisely “among” woolen fibres” and thereby warmed, closely follows the wording of Melville’s source-text. His next bit of information, establishing the warming effect of winter snow, paraphrases yet another Q-and-A pair in the same section, #1480 in Familiar Science, page 396.

Q. Does snow keep the earth warm?

A. Yes, because it is a very bad conductor; in consequence of which, when the earth is covered with snow, its temperature very rarely descends below freezing point, even when the air is fifteen or twenty degrees colder.

BLANDMOUR

Just so, then, take the temperature of a December field when covered with this snow-fleece, and you will no doubt find it several degrees above that of the air.

In the voice of Blandmour, a poet, Melville makes Dr. Brewer’s essential point in more colorful and suitably poetic language. Melville has transformed the season “when the earth is covered with snow” into more of a cozy winter wonderland—representing earth as a charming “December field” blanketed not merely by snow but “snow-fleece.” In a rhetorical flourish, Blandmour invites the narrator to “take the temperature” himself, In this manner Melville has inventively personalized the objective contrast in his source-text between relative temperatures of earth and air in winter.

Benefits of bad ventilation

Melville’s narrative “Picture” in “Poor Man’s Pudding” starts and ends with creative borrowings from some version of Ebenezer Cobham Brewer’s popular Guide to familiar science.

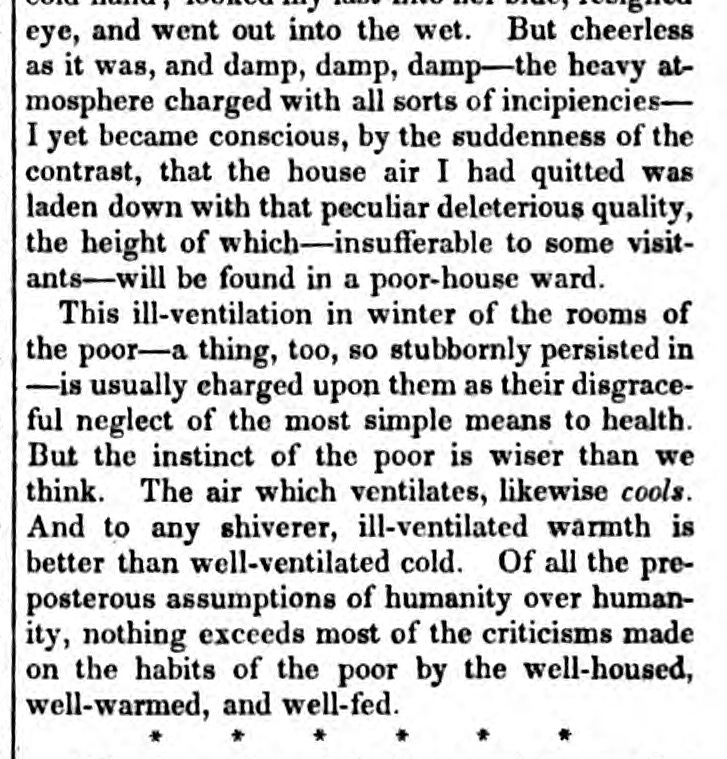

Near the close of “Poor Man’s Pudding,” the narrator records his observation of the oppressively “damp” and “heavy” air in the Coulters’ home, and then generalizes about the badly ventilated rooms that poor people too often inhabit, especially in winter. Invoking some imaginary abuser (maybe Malthus) of the poor and their alleged “instinct” for “ill-ventilation,” Melville’s narrator protests in their defense that stale indoor air has one great advantage “to any shiverer” in being warmer than air circulated and cooled through ventilation.

This ill-ventilation in winter of the rooms of the poor—a thing, too, so stubbornly persisted in—is usually charged upon them as their disgraceful neglect of the most simple means to health. But the instinct of the poor is wiser than we think. The air which ventilates, likewise cools. And to any shiverer, ill-ventilated warmth is better than well-ventilated cold.

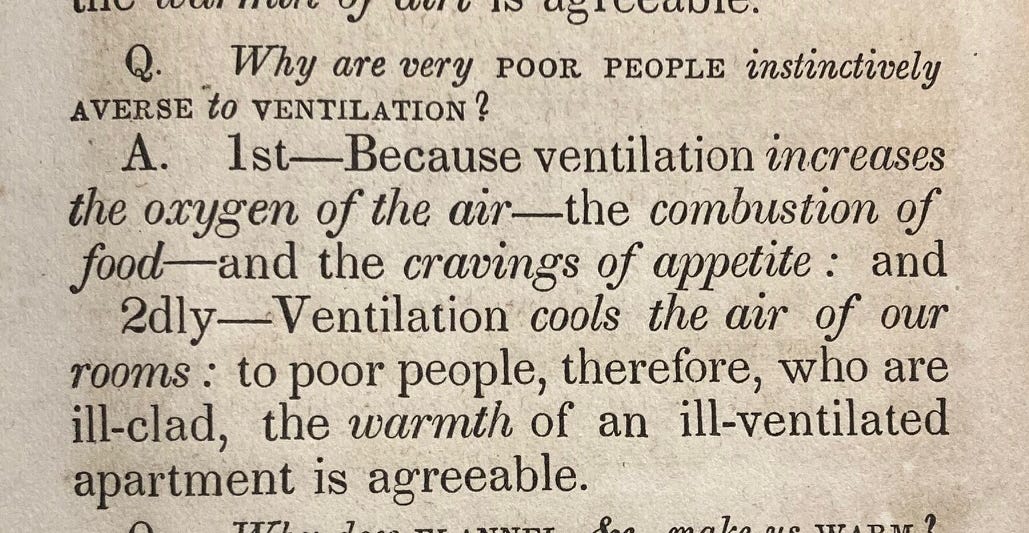

Rather than evincing habitual neglect of good health, as ostensibly alleged by unnamed critics, the observed preference for bad ventilation in winter results from the natural human “instinct” to keep warm. Thus reasons Melville’s compassionate narrator, who takes his theme directly from Dr. Brewer’s section on “Animal Heat,” #1115 in Peterson’s Familiar Science. Image below reproduces the same Q-and-A as it appears on page 93 of A Guide to the Scientific Knowledge of Things Familiar (New York: C. S. Francis & Co. and Boston: Crosby, Nichols & Co., 1854).

Q. Why are very POOR PEOPLE instinctively AVERSE to VENTILATION ?

A. 1st—Because ventilation increases the oxygen of the air—the combustion of food and the cravings of appetite : and

2dly—Ventilation cools the air of our rooms : to poor people, therefore, who are ill-clad, the warmth of an ill-ventilated apartment is agreeable.

In paraphrasing his source-text near the end of “Poor Man’s Pudding,” Melville has disregarded the first part of Dr. Brewer’s answer. Instead of bothering about scientific processes of oxygenation and combustion, Melville keys on the second part, about ventilation. As the latter part of the answer in Familiar Science #1115 explains, “poor people” without adequate clothing to wear actually prefer rooms without good air circulation for their relative warmth, in contrast to rooms that are better ventilated and therefore colder.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1115

Ventilation cools the air of our rooms :

MELVILLE

The air which ventilates, likewise cools.

Melville’s rewrite turns Brewer’s word ventilation into a verb, making the grammar of “ventilates” parallel to that of “cools.” Both the original and Melville’s rewrite have the word cools in italics.

The rest of the paraphrase features another parallelism created through revision of Melville’s source-text. Melville copied “ill-ventilated” from his source in Brewer’s Guide page 93 or Familiar Science #1115, and added “well-ventilated” to yield contrasting, parallel descriptors. He strengthened the parallelism through antithesis by copying the noun “warmth” and adding “cold” to sharpen the contrast in fresh, perfectly parallel phrases: “ill-ventilated warmth” vs. “well-ventilated cold.”

FAMILIAR SCIENCE #1115

… to poor people, therefore, who are ill-clad, the warmth of an ill-ventilated apartment is agreeable.

MELVILLE

And to any shiverer, ill-ventilated warmth is better than well-ventilated cold.

Another addition is the figure of “any shiverer,” one of the best changes Melville made to his source-text in some version of Dr. Brewer’s handy guidebook of popular science. When creatively rewriting source material, Melville often gravitates to the concrete and personal. In this case, where his source generalized about the predicament of “ill-clad” poor people. Melville individualizes the point of view, changing the perspective from that of “poor people” in the abstract to that of “any shiverer.” At the same, the construction invites empathy by appealing to a relatable experience of common humanity. In the image of “any shiverer,” Melville has visualized how any person, not excluding any reader, might feel and act in a cold apartment, with no winter clothes.

Poor Man’s Pudding,” was probably composed in late 1853 or early 1854 according to Merton M. Sealts, Jr. in his “Chronology of the Short Fiction,” Pursuing Melville, 1940-1980 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982) pages 221-231 at 228; incorporated in The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces, 1839-1860, ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, G. Thomas Tanselle, and others (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 1987) page 493. “The Lightning-Rod Man” was first published in Putnam’s for August 1854, two months after “Poor Man’s Pudding” appeared in Harper’s magazine.

Historian Bernard Lightman calls Brewer’s well-received guidebook a “scientific catechism” in Victorian Popularizers of Science: Designing Nature for New Audiences (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2007) page 67.